So here’s a fun one: how does the unsafe-hashes directive in a content security police work?

In a perfect world, you don’t need it. You can write a CSP with a minimal script-src policy, including only scripts from your own domains (self) or a list of specific other scripts or at worst domains.

But sometimes real life (and third party libraries) get in the way.

It starts with inline scripts. So you have to add unsafe-inline. But there’s a better way to do that: CSP nonces. Specify a randomly generated (per request) nonce in the CSP header and then apply that same nonce to every script tag. Voila. Better.

The problem: inline JavaScript events

But what about something like this:

<button onClick="doSomething();">

Well, you might say, don’t do that. Write it as a script:

<button id="doSomethinger">

<script nonce="correctHorseBatteryStable">

document.getElementById("doSomethinger").addEventListener("click", function() {

doSomething();

});

</script>

But like I said–third parties scripts can be imperfect. And sometimes, they just insist on embedding their own event handlers inline.

A solution: unsafe-hashes

Enter: unsafe-hashes.

Basically, you can add this to your CSP:

script-src 'unsafe-hashes' 'sha256-44558f2c36efd8163eac2903cec13ed1fafcca51abd91d9f696321ab895f1107'

This tells the browser that you are allowed to have event listeners directly on HTML elements… so long as the content of the JavaScript hashes exactly to any hash listed as an unsafe-hash:

$ echo -n "doSomething();" | sha256

44558f2c36efd8163eac2903cec13ed1fafcca51abd91d9f696321ab895f1107

It gets worse: dynamically generated JavaScript

There is, however, one problem with this that does come up unfortunately often. If you’re already dealing with third parties not doing things you wish they would, well then you have to deal with fun code like this:

<?php

foreach ($buttonIds as $buttonId) {

echo '<button onclick="doSomething(' . $buttonId . ');">Button ' . $buttonId . '</button>' . PHP_EOL;

}

?>

Unfortunately… that completely blows up the CSP. Because…

$ echo -n "doSomething(1);" | sha256

2ef899c15aae95711855a45a5bb93c55363162e0e75e295aad4f189f20323d7c

$ echo -n "doSomething(5);" | sha256

0e03bb385169b89c95eb62659f50604ffb8283154bd58ab8cc7e692c4b5c05a3

$ echo -n "doSomething(42);" | sha256

4d9691449db6740ee19207c5bb52361eb97e18f06352ed400f83ae7caee270da

Just hashes doing hash things there. So basically, you have to be able to dynamically generate your CSP on the fly, including all of the hashes of all of the functions and with each of their arguments that are either possible or (even better) actually used.

And this isn’t fun at all.

Now, you might say: but you can do something like this:

<?php

foreach ($buttonIds as $buttonId) {

echo '<button data-id="$buttonId" onclick="doSomething(this.dataset.id);">'

}

?>

After all

$ echo -n "doSomething(this.dataset.id);" | sha256

d2ecabb98b1bb7cc81cd75d43dcb7bac08ce31055339920976cb92aa2f5dd2f5

Only one hash!

But if you have that much control… then why are you using inline JavaScript in the first place?

Is it safe?

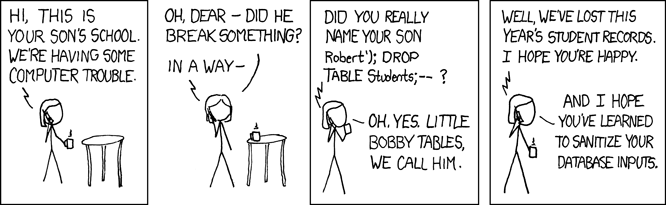

Is this safe?

No. It’s called unsafe-* for a reason. An attacker that controls input can theoretically take any of the hashed functions you’re including (like submitPayment…) and inject them in places they shouldn’t be. And heck, if you manage to find a SHA-256 hash collision? Well, then you have far more interesting things to do with that then attacking some site that found themselves force to used unsafe-hashes…

But it’s better than unsafe-inline without nonces which allows arbitrary inline scripts. And unfortunately, there’s no way to actually use nonces with inline scripts.

And while a perfectly secure system would be the best case, it’s absolutely better to do as much as you can to secure a system rather than doing nothing waiting for the perfect solution to become possible.

Onward!