Cephalopods are an island of mental complexity in the sea of invertebrate animals. Because our most recent common ancestor was so simple and lies so far back, cephalopods are an independent experiment in the evolution of large brains and complex behavior. If we can make contact with cephalopods as sentient beings, it is not because of a shared history, not because of kinship, but because evolution built minds twice over. This is probably the closest we will come to meeting an intelligent alien.

Octopuses1 are perhaps the best known example of what might be a truly alien intelligence on Earth. They’re far further from humanity than primates or dolphins or even birds. And man. They’re weird.

This book digs into the history of life itself, the beginning of what would eventually become brains, and how life eventually split and branched into all the myriad forms we have today.

In the Ediacaran, other animals might be there around you, without being especially relevant. In the Cambrian, each animal becomes an important part of the environment of others. This entanglement of one life in another, and its evolutionary consequences, is due to behavior and the mechanisms controlling it. From this point on, the mind evolved in response to other minds.

This part? Very interesting.

We also get some fascinating discussions about some of the weirder things octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish do. Color changing, shape shifting, and independently acting arms. They have it all.

Suppose some light-sensitive cells sit below a layer of many chromatophores. As chromatophores of different colors expanded and contracted, the light passing through them would be affected in different ways. If the animal kept track of which chromatophores were expanded, as well as how much light was reaching its sensors, it could know something about the color of incoming light.

Also cool.

Octopus society. A surprisingly short lived and solitary species, and yet still in one case, they’ve actually built something of a city in the ocean off Australia.

A marine research unit at Monterey Bay, California (MBARI), explores deep-sea environments with remote-controlled submarines that carry video cameras. In 2007 they were inspecting a rocky outcrop nearly a mile underwater, off the coast of central California. They saw a deep-sea octopus (Graneledone boreopacifica) moving around. Returning a month or so later, they found the same octopus guarding a clutch of eggs. They kept returning to the site to watch the progress of this clutch of eggs, and always found the octopus there. In the end they watched this one octopus for four and a half years. This octopus brooded her eggs for longer than any other known octopus is thought to live in total, and the fifty-three months it spent there is the longest egg-brooding period reported for any animal species.

Fascinating.

And then also a dive into consciousness. Which… we can barely explain or define what consciousness means for people, let alone verify it’s presence in any other species.

It’s entirely philosophical and not really my domain. Philosophy is weird and malleable and hard (at best) to actually put to scientific scrutiny. We can certainly measure some aspects of intelligence and communication and tool using among non-human species… but how in the world to you ask an octopus what it thinks about thinking? How in the world do you tell if they’re actually aware of their self and surroundings?

The second thing Hume missed is more conspicuous. When we look inside, most people find a flow of inner speech2, a monologue that accompanies much of our conscious life. Sentences and phrases, exclamations, rambling commentaries, speeches we would like to give, or wish we’d given. Maybe Hume did not find this in his own case? Some people have a more prominent inner monologue than others. Perhaps Hume was one of those for whom inner speech is weak? It’s possible, but I think it’s more likely that Hume did encounter inner speech, but regarded it as one part of the wash of sensations, not as anything special. There are colors and shapes and emotions in there, and echoes of speech as well.

This whole part was a bit weird–which, being in the title, is kind of weird. I’m not entirely sure what I was expecting, but somehow… more?

And then… it ends. A lot of appendices and references meant the book ended rather before I expected.

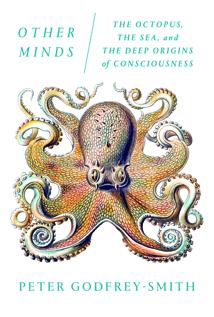

A decent book with a delightful cover and a number of fun octopus facts I’d never heard before. Worth reading just for that.

Onward!

If you’ve made it this far?

(Warning, probably not safe for children.)

😄