I am fond of the quote “When you’ve met one Aspergian, you’ve met one Aspergian. We are all unique.” That may be true, but now that I’m meeting other Aspergians, I am finding that some traits I thought were unique to me are actually characteristic of Aspergians.

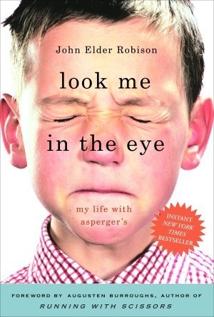

John Robison–John Elder–grew up with autism (or what would once have been diagnosed as Aspergers before DSM-5). He was always an odd kid and had to grow up quick and come up with all manner of interesting coping mechanisms to survive in a world that wasn’t entirely sure how to deal with him.

It doesn’t help that he had an… interesting home life, also described by his brother in the memoir Running with Scissors–and later planted the seed that grew into Look Me in the Eye.

You should write a memoir. About Asperger’s, about growing up not knowing what you had. A memoir where you tell all your stories. Tell everything.” About five minutes later, he e-mailed me a sample chapter. “Like this?” was the subject line of the e-mail. Yes. Like that. Once again, my brilliant brother had found a way to channel his unstoppable Asperger energy and talent. When he decided to research our family history and create a family tree, the document ended up being more than two thousand pages long. So once the idea of writing a memoir was in his head, he dove in with an intensity that would send most people straight into a psychiatric hospital.

Although found that although people didn’t always do what he expected, electronics most certainly did. This lead to quite the career, building, repairing, and upgrading sound systems, including building a lot of the custom hardware used by the band KISS–and then later also getting into designing the electronics in toys and eventually repairing expensive cars.

Certainly not where I expected his story to go, I’ll say that much, but the way he describes the story, each step just makes so much sense.

Another fascinating half of the book (to me) is hearing John Elder describe the world he lives in. I’ll go into more specifics in a later section, but this was really the part of the book that stood out to me. Like the quote says/implies, every is different–and those with autism are no exception… but that doesn’t mean that people who’s brains tend the same way might just see the world the same way. Some of these things I’ve never seen put into words before. Worth the read just for that.

Overall, I quite enjoyed this book. If you have autism (diagnosed or not)–or if you know someone with autism (and I expect you do, even if you don’t know it), I recommend giving it a read. Perhaps you’ll see something of yourself in it.

Aspergian traits

Okay, it’s a bit much, but I wanted to share some specific traits John Elder describes in the book that I found fascinating.

Visual (and otherwise) noise

To this day, when I speak, I find visual input to be distracting. When I was younger, if I saw something interesting I might begin to watch it and stop speaking entirely. As a grown-up, I don’t usually come to a complete stop, but I may still pause if something catches my eye. That’s why I usually look somewhere neutral—at the ground or off into the distance—when I’m talking to someone. Because speaking while watching things has always been difficult for me, learning to drive a car and talk at the same time was a tough one, but I mastered it.

There’s certainly something to be said for distraction. And sometimes the inability to filter out stimuli as well as a neurotypical person can. So this both helps to answer why ’look me in the eye’ can be a difficult ask and why loud/bright/etc situations are difficult.

Pressure and weighted blankets

I liked squeezing myself up tight in a tiny ball when I was little, hiding where no one could see me. I still like the feeling of lying under things and having them press on me. Today, when I lie on the bed I’ll pile the pillows on top of me because it feels better than a sheet.

Weighted blankets, yo. I wonder if he’s ever tried one.

Empathy

I have what you might call “logical empathy” for people I don’t know. That is, I can understand that it’s a shame that those people died in the plane crash. And I understand they have families, and they are sad. But I don’t have any physical reaction to the news. And there’s no reason I should. I don’t know them and the news has no effect on my life. Yes, it’s sad, but the same day thousands of other people died from murder, accident, disease, natural disaster, and all manner of other causes. I feel I must put things like this in perspective and save my worry for things that truly matter to me.

That’s such a wonderful way of describing it. To understand that you should care and that others will care… but finding it hard to find it in yourself when it’s all just out there somewhere.

Until it isn’t. And sometimes it all comes home in unexpected ways–jumping to thinking about how it could be a family member or the like.

Those with autism don’t always/often lack empathy. They just feel/express it differently.

Naming

I named her Little Bear. Her mother called her Mary Lee—Lee being her middle name—or Baby Daughter, but those names would never do for me. For some reason, I have always had a problem with names. For people that are close to me, for example, I must name them myself. Sometimes I would call her Baby Daughter to tease her, but she always got mad, and I eventually gave up. Little Bear was what she remained.

I don’t think I’ve ever heard the naming thing described anywhere else. I have the hardest time reading books sometimes, since I can never seem able to remember which name goes with which character–especially if they’re at all similar.

Nicknames help. Titles and descriptions help.

This is also one reason I found Annihilation fascinating. None of the characters in the book are ever named!

Touch

If I wake up, she puts a paw on me and I go back to sleep. I put a paw on her, too. Sometimes I wake in the night, and find we have rolled apart. We’ll be sleeping on our sides, facing in opposite directions. I’ll slide over until our backs are touching, and I’ll slide my bent legs back toward her. She’ll awaken enough to reach her own foot over, and our feet will touch. I fall back asleep, content and warm.

John Elder’s descriptions of more ‘animal-like’ behavior are interesting (he otherwise describes wanting to / feeling calm when being petted). But just that little touch…

Speech patterns

Since that time, I’ve talked to hundreds of people on the spectrum, as well as their parents. It has become clear that there is indeed “a voice of Asperger’s,” and that I have it. But what is it, precisely? The answer came to me last winter, during a visit with some brilliant researchers from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, a part of Harvard Medical School. They’d been studying autism and the workings of the brain, and they gave me some startling insights. It turns out that sentences are not formed in a single area of the brain. It’s far more complex than that. We form the concept of a sentence in one spot. Then we choose the verbs in another area and nouns in yet a third spot. The sentence is built in pieces throughout the brain, and then assembled into finished form. For some reason, Aspergians like me experience “delays” in the transmission of those sentence fragments within the brain. That gives a slightly ragged cadence to our speech that’s quite distinct from that of normal speech. Once you begin listening for it, it’s quite recognizable.

Well that’s interesting. Language is a tricky one. And it’s especially interesting to see how it changes as one gets tired/loses ’extra capacity’.