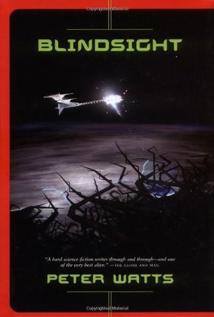

Vampires. In space.

It’s not at all what I expected, but at the same time, kind of awesome. I mean, look how it starts:

You wake in an agony of resurrection, gasping after a record-shattering bout of sleep apnea spanning one hundred forty days. You can feel your blood, syrupy with dobutamine and leuenkephalin, forcing its way through arteries shriveled by months on standby. The body inflates in painful increments: blood vessels dilate, flesh peels apart from flesh, ribs crack in your ears with sudden unaccustomed flexion. Your joints have seized up through disuse. You’re a stick man, frozen in some perverse rigor vitae.

…

Vampires did this all the time, you remember. It was normal for them, it was their own unique take on resource conservation. They could have taught your kind a few things about restraint, if that absurd aversion to right angles hadn’t done them in at the dawn of civilization. Maybe they still can. They’re back now, after all—raised from the grave with the voodoo of paleogenetics, stitched together from junk genes and fossil marrow steeped in the blood of sociopaths and high-functioning autistics. One of them commands this very mission. A handful of his genes live on in your own body so it too can rise from the dead, here at the edge of interstellar space. Nobody gets past Jupiter without becoming part vampire.

This is just a cool concept. The entire idea that vampires are real. The justification that they evolved torpor/hibernation to deal with not out-compenting and wiping out humanity. A natural aversion (leading to seizures) when viewing right angles (like… crosses) that isn’t weeded out because nature doesn’t have many right angles. Super hardy, high processing, great for space travel.

It’s so cool.

And on top of that, we have virtual worlds, the Chinese room argument (with an entire character base on it), normalization of multiple personalities, and all sorts of other interesting people and brains on the trip. Every single one of them is atypical in some way (or multiple ways) and digging into that is a large part of the book.

And we haven’t even gotten to the aliens yet.

All in all, it’s a whole bunch of fascinating concepts all packed into a gloriously dense book. I could see any one of these carrying a novel, let alone all of them. The setting being deep space on (or beyond) the edge of the solar system makes everything claustrophobic, while the flashes of backstory give a bit of time to recover (and explain what in the world is going on with some of these characters).

I really enjoyed it. If any of the above intrigues you, give it a try. I will say though; warning: this is a weird book. Your milage may vary.

Onward!

My notes (potential spoilers):

Give it a big enough matter stockpile and it could have even built another Theseus, albeit in many small pieces and over a very long time. Some wondered if it could build another crew as well, although we’d all been assured that was impossible. Not even these machines had fine enough fingers to reconstruct a few trillion synapses in the space of a human skull. Not yet, anyway.

3d printed crew. Also it’s delightful the ship is named Theseus.

But we’re not very good at building them. The forced matings of minds and electrons succeed and fail with equal spectacle. Our hybrids become as brilliant as savants, and as autistic. We graft people to prosthetics, make their overloaded motor strips juggle meat and machinery, and shake our heads when their fingers twitch and their tongues stutter. Computers bootstrap their own offspring, grow so wise and incomprehensible that their communiqués assume the hallmarks of dementia: unfocused and irrelevant to the barely-intelligent creatures left behind.

Early cybernetic life too?

It was at first. How many intersecting right angles do you see in nature?” He waved one dismissive hand. “Anyway, that’s not the point. The point is they can do something that’s neurologically impossible for us Humans. They can hold simultaneous multiple worldviews, Pod-man. They just see things we have to work out step-by-step, they don’t have to think about it. You know, there isn’t a single baseline human who could just tell you, just off the top of their heads, every prime number between one and a billion? In the old days, only a few autistics could do shit like that.

This continues to be fascinating. Vampires and right angles and worldviews. Autistic.

“Diver farts. Those bastards are dumping complex organics into the atmosphere.”

“How complex?”

“Hard to tell, so far. Faint traces, and they dissipate like that. But sugars and aminos at least. Maybe proteins. Maybe more.”

“Maybe life? Microbes?” An alien terraforming project …”

Panspermia?

Once there were three tribes. The Optimists, whose patron saints were Drake and Sagan, believed in a universe crawling with gentle intelligence—spiritual brethren vaster and more enlightened than we, a great galactic siblinghood into whose ranks we would someday ascend. Surely, said the Optimists, space travel implies enlightenment, for it requires the control of great destructive energies. Any race that can’t rise above its own brutal instincts will wipe itself out long before it learns to bridge the interstellar gulf.

Across from the Optimists sat the Pessimists, who genuflected before graven images of St. Fermi and a host of lesser lightweights. The Pessimists envisioned a lonely universe full of dead rocks and prokaryotic slime. The odds are just too low, they insisted. Too many rogues, too much radiation, too much eccentricity in too many orbits. It is a surpassing miracle that even one Earth exists; to hope for many is to abandon reason and embrace religious mania. After all, the universe is fourteen billion years old: If the galaxy were alive with intelligence, wouldn’t it be here by now?

Equidistant to the other two tribes sat the Historians. They didn’t have too many thoughts on the probable prevalence[…]”

That’s a fun way to think about it.

So I thought about it, and I came up with the perfect way to raise her awareness. I wrote her a bedtime story, a disarming blend of humor and affection, and I called it:

The Book of Oogenesis

In the beginning were the gametes. And though there was sex, lo, there was no gender, and life was in balance.

And God said, “Let there be Sperm”: and some seeds did shrivel in size and grow cheap to make, and they did flood the market

And God said, “Let there be Eggs”: and other seeds were afflicted by a plague of Sperm. And yea, few of them bore fruit, for Sperm brought no food for the zygote, and only the largest Eggs could make up the shortfall. And these grew yet larger in the fullness of time.

That is so weird.

It was a blizzard, not a briefing: gravity wells and orbital trajectories, shear stress simulations in thunderheads of ammonium and hydrogen, stereoscopic planetscapes buried under filters ranging from gamma to radio. I saw breakpoints and saddle-points and unstable equilibria. I saw fold catastrophes plotted in five dimensions. My augments strained to rotate the information; my meaty half-brain struggled to understand the bottom line.

I love both the idea of brain augmentations struggling to keep up and the way it’s written.

“She’d had less than three minutes. Or rather, they’d had less than three minutes: four fully-conscious hub personalities and a few dozen unconscious semiotic modules, all working in parallel, all exquisitely carved from the same lump of gray matter. I could almost see why someone would do such deliberate violence to their own minds, if it resulted in this kind of performance.”

Another neat concept. Makes you wonder in this world or ours, what the brain might be capable of. The 10% thing is bull, but can we learn/grow more capacity?

“Maybe it should be. We, at least”—he waved an arm; some remote-linked sensor cluster across the simulator whirred and torqued reflexively—”chose the add-ons. Vampires had to be sociopaths. They’re too much like their own prey—a lot of taxonomists don’t even consider them a subspecies, you know that? Never diverged far enough for reproductive isolation. So maybe they’re more syndrome than race. Just a bunch of obligate cannibals with a consistent set of deformities.”

This in an otherwise sci-fi story is just fascinating.

“Sascha,” Bates breathed. “Are you crazy?”

“So what if I am? Doesn’t matter to that thing. It doesn’t have a clue what I’m saying.”

“What?”

“It doesn’t even have a clue what it’s saying back,” she added.

“Wait a minute. You said—Susan said they weren’t parrots. They knew the rules.”

And there Susan was, melting to the fore: “I did, and they do. But pattern-matching doesn’t equal comprehension.”

It’s ChatGPT.

“Michelle’s—I mean, yes, you’re all very different facets, but there’s only one original. Your alters—”

“Don’t call us that.” Sascha erupted with a voice cold as LOX. “Ever.”

Szpindel tried to pull back. “I didn’t mean—you know I didn’t—”

An interesting reaction.

“WE WERE PROBABLY fractured during most of our evolution,” James once told me, back when we were all still getting acquainted. She tapped her temple. “There’s a lot of room up here; a modern brain can run dozens of sentient cores without getting too crowded. And parallel multitasking has obvious survival advantages.”

It’s sort of the opposite idea of the Bicameral mind and another interesting theory. I don’t know of anything to support it and I assume it would have been at least mentioned in writings of the time. But if it were normal, perhaps not?

“A soft hum started up somewhere between my ears. Chelsea’s voice led me on through the darkness. “Now keep in mind, memories aren’t historical archives. They’re—improvisations, really. A lot of the stuff you associate with a particular event might be factually wrong, no matter how clearly you remember it. The brain has a funny habit of building composites. Inserting details after the fact. But that’s not to say your memories aren’t true, okay? They’re an honest reflection of how you saw the world, and every one of them went into shaping how you see it. But they’re not photographs. More like impressionist paintings.”

Understandable. Still surreal.

There was more, a whole catalog of finely-tuned dysfunctions that Rorschach had not yet inflicted on us. Somnambulism. Agnosias. Hemineglect. ConSensus served up a freak show to make any mind reel at its own fragility: a woman dying of thirst within easy reach of water, not because she couldn’t see the faucet but because she couldn’t recognize it. A man for whom the left side of the universe did not exist, who could neither perceive nor conceive of the left side of his body, of a room, of a line of text. A man for whom the very concept of leftness had become literally unthinkable.

Brains are really weird.

“Vision’s mostly a lie anyway,” he continued. “We don’t really see anything except a few hi-res degrees where the eye focuses. Everything else is just peripheral blur, just … light and motion. Motion draws the focus. And your eyes jiggle all the time, did you know that, Keeton? Saccades, they’re called. Blurs the image, the movement’s way too fast for the brain to integrate so your eye just … shuts down between pauses. It only grabs these isolated freeze-frames, but your brain edits out the blanks and stitches an … an illusion of continuity into your head.””

Adequately awesome and (given the context of the book) terrifying all at once.

“Yet the questions persisted, in the minds of the laureates, in the angst of every horny fifteen-year-old on the planet. Am I nothing but sparking chemistry? Am I a magnet in the ether? I am more than my eyes, my ears, my tongue; I am the little thing behind those things, the thing looking out from inside. But who looks out from its eyes? What does it reduce to? Who am I? Who am I? Who am I?

What a stupid fucking question. I could have answered it in a second, if Sarasti hadn’t forced me to understand it first.”

I love it.

“You’re not thinking this through,” Cunningham said. “We’re not talking about some kind of zombie lurching around with its arms stretched out, spouting mathematical theorems. A smart automaton would blend in. It would observe those around it, mimic their behavior, act just like everyone else. All the while completely unaware of what it was doing. Unaware even of its own existence.””

A fascinating philosophical concept. At a weird time and place.

“It’s a matter of degree and you know it. Even in a crowd there’s a certain expectation of privacy. People aren’t prepared to have their minds read off every twitch of the eyeball.” He stabbed at the air with his cigarette. “And you. You’re a shapeshifter. You present a different face to every one of us, and I’ll wager none of them is real. The real you, if it even exists, is invisible …”

Something knotted below my diaphragm. “Who isn’t? Who doesn’t … try to fit in, who doesn’t want to get along? There’s nothing malicious about that. I’m a Synthesist, for God’s sake! I never manipulate the variables.””

That certainly sounds like masking writ large. I wonder if they’ll go into it. They did a bit with vampires at least.

There are no meaningful translations for these terms. They are needlessly recursive. They contain no usable intelligence, yet they are structured intelligently; there is no chance they could have arisen by chance.

The only explanation is that something has coded nonsense in a way that poses as a useful message; only after wasting time and effort does the deception becomes apparent. The signal functions to consume the resources of a recipient for zero payoff and reduced fitness. The signal is a virus.

Viruses do not arise from kin, symbionts, or other allies.

The signal is an attack.

And it’s coming from right about there.

Huh.

That’s delightfully alien.