This is an exercise in fictional science, or science fiction, if you like that better. Not for amusement: science fiction in the service of science. Or just science, if you agree that fiction is part of it, always was, and always will be as long as our brains are only minuscule fragments of the universe, much too small to hold all the facts of the world but not too idle to speculate about them.

What am I in for…

Overall, it’s an interesting read. In a nutshell, it builds up a model for ‘vehicles’ that start with a single wheel and basic sensor and grows, adding better senses and in particular a more and more complicated brain. I would have liked something a bit more technical and/or practical but there are a lot of interesting ideas here.

One downside, the wording is … a bit pretentious at times. Academic is probably a better word. Above is the first paragraph.. and that’s really how it stays.

Overall, an interesting enough and surprisingly quick read.

Thoughts as I read:

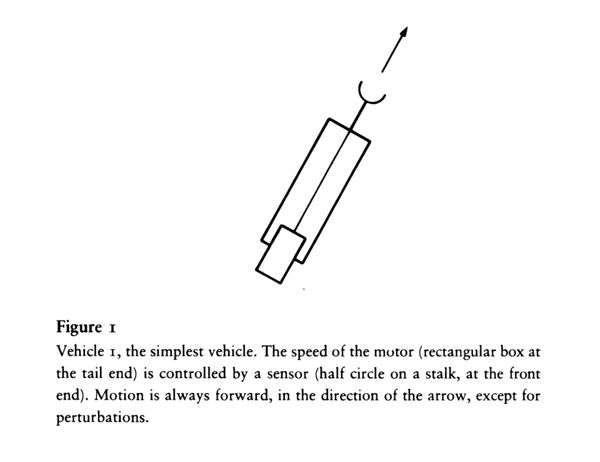

Vehicle 1: Getting Around

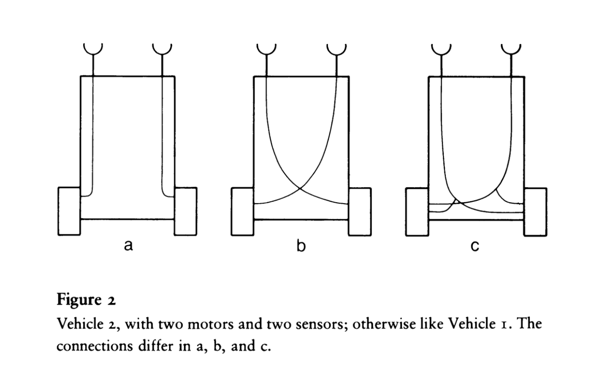

Vehicle 2: Fear and Aggression

2a will tend to overcorrect, turning away from it’s sensors. 2b on the other hand will turn unerringly towards its target.

Vehicle 3: Love

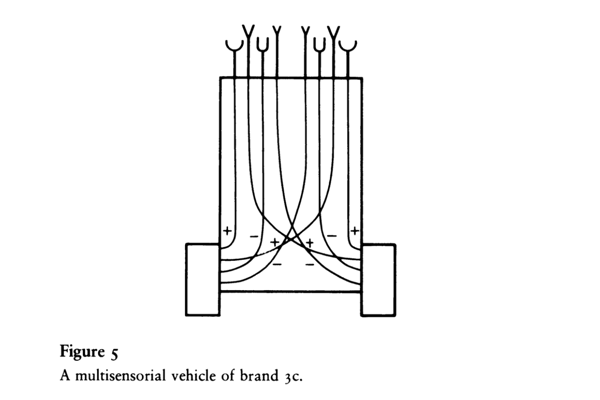

Adding multiple sensors and the ability to invert them has given this vehicle the ability to rank and respond differently to different inputs.

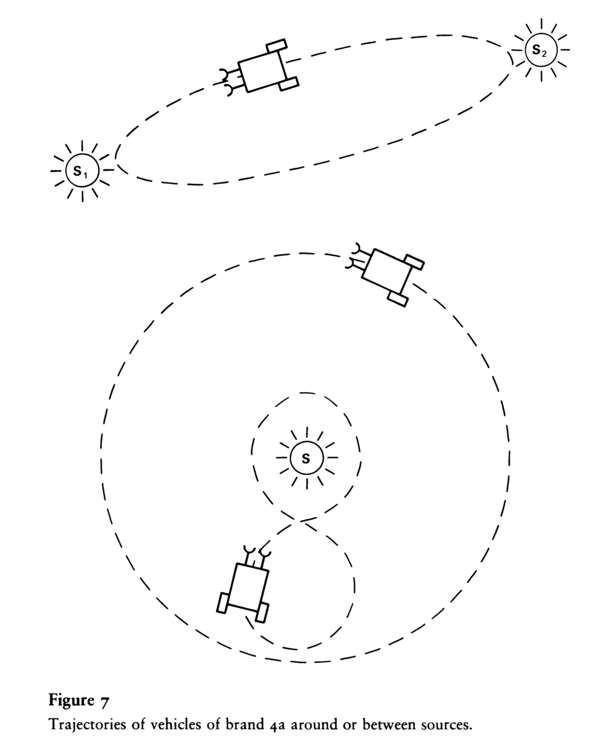

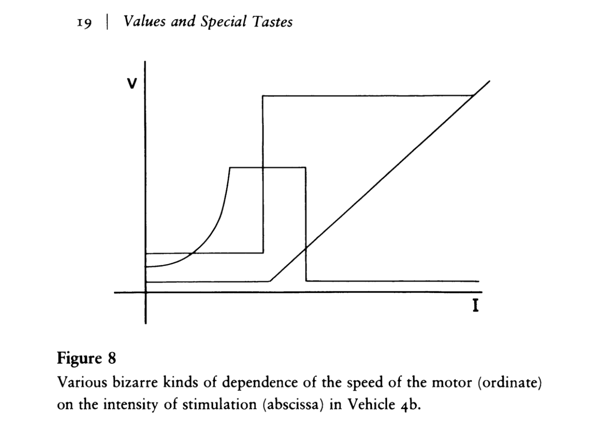

Vehicle 4: Values and Special Tastes

Make responses nonlinear. Specially in this case, a bell curve. This will tend to produce vehicles that would prefer to stay at a certain distance, creating orbits and similar patterns.

Of course, you can get even more interesting than bell curves for activation functions…

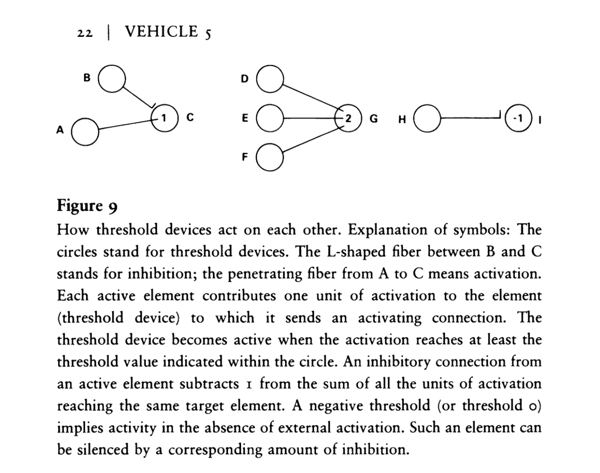

Vehicle 5: Logic

And then suddenly… neutral networks!

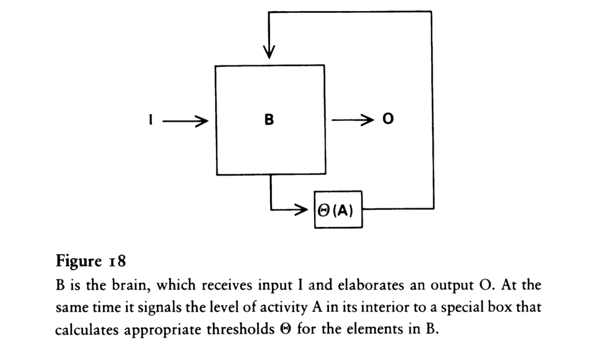

Specially, a graph of ‘threshold devices’ that pass zero below a threshold or their input above. One neat trick: because the graph isn’t limited to layers of neurons, we ahead have recurrence and thus memory.

Vehicle 6: Selection, the Impersonal Engineer

Wherein Darwinian evolution/genetic algorithms are described, albeit in a target guided mode (No direct crossover or mutation, the new vehicles are assembled by hand.)

Vehicle 7: Concepts

Now change the wiring so that you can turn on and off wires dynamically, making programmatic behavior within an individual’s lifetime (rather than via evolution).

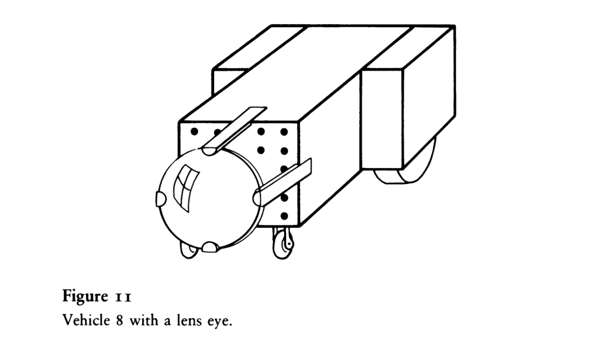

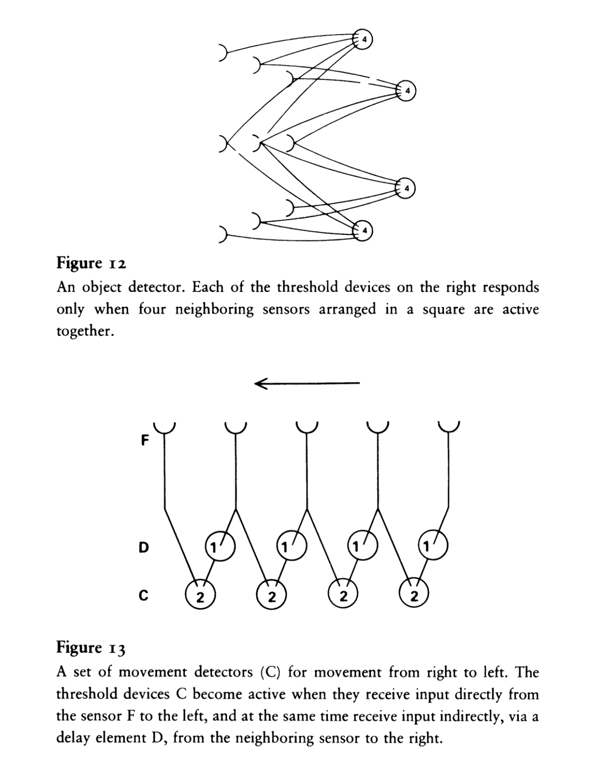

Vehicle 8: Space, Things, and Movement

Upgrade the sensors to eyes! Now with more than analogue resolution!

This lets us detect objects or, with the previously described memory circuits, motion.

Vehicle 9: Shapes

Edge detection follows from vehicle 8 above; if you can detect high_low_high you can detect edges. But now, we expand that into symmetry (lateral and radial) and shapes.

Vehicle 10: Getting Ideas

But do they think? I must frankly admit that if anybody suggested that they think, I would object. My main argument would be the following: No matter how long I watched them, I never saw one of them produce a solution to a problem that struck me as new, which I would gladly incorporate in my own mental instrumentation. And when they came up with solutions I already knew, theirs never reminded me of thinking that I myself had done in the past. I require some originality in thinking. If it is lacking, I call the performance at best reasonable behavior. Even if I do observe a vehicle displaying a solution to a problem that would not have occurred to me, I do not conclude that the vehicle is thinking; I would rather suppose that a smart co-creator of vehicles had built the trick into the vehicle. I would have to see the vehicle’s smartness arising out of nothing, or rather, out of not-so-smart premises, before I concluded that the vehicle had done some thinking.

I think there’s an interesting question here, but this doesn’t really help the matter one way or the other. What does it mean to think versus running some inherent algorithm? How do we know that we think.

‘New’ solutions is a reasonable enough explanation, but how do you know something is new? How do you know it’s not an unexpected extension to the existing programming?

Vehicle 11: Rules and Regularities

Most of you will not yet be convinced that the process of getting ideas as it was described in the previous chapter has anything to do with thinking. It is not surprising, you will say, that occasionally something clicks in the workings of a fairly complicated brain and from then on that brain is able to perform a trick (an algorithm, as some people say) that can be used to generate complicated sequences of numbers or of other images. It is also not surprising that these may occasionally match sequences of events or things in the world of the vehicle.

Heh.

Upgrading variable wires with a time component: this ends up introducing causality. Although I feel this could have been built with the previous wires and memory components, but perhaps I’m jumping ahead?

On the other hand, purely descriptive classification is not only boring, it is also potentially misleading. It may lead to the wrong categories when it is not guided by at least the intuition of a theory of the underlying processes. A century of microscopic anatomy has filled the libraries with thousands of beautifully illustrated volumes that are now very rarely consulted because the descriptive categories of the old histology have been largely superseded by the new concepts of biochemical cytology. The example from linguistics that we have just mentioned may well serve to prove the contrary point, with word roots—morphemes—words as the segments of speech that must be learned. While it is true that these chunks of meaning in some languages (largely in English) coincide with acoustically well-defined episodes (the syllables, which the naive listener can recognize), it is certainly true that a better, more general definition of morphemes or words is derived from grammar. Words (I use this term loosely) are the segments of speech that we discover as the ultimate particles of grammar. If we had no idea or no experience of grammar, we might never discover that these are the pieces that are shuffled around to form sentences. We might propose a different, incorrect segmentation of speech, for example, a segmentation into syllables in a language with polysyllabic words. Words become meaningful insofar as they are used in a grammatical system.

And now for a quick interlude into linguistics. It’s an interesting discussion—what are the roots of meaning in language—but a bit odd in context.

Vehicle 12: Trains of Thought

Turns out, our imaginary machines could suffer from epilepsy. Put in a global governance circuit to stop that.

I hope you realize what this means. If you could observe the inner workings of the vehicle’s brain, say, by watching light bulbs connected to the threshold devices, and these light bulbs lit up every time the corresponding element became active, you could not even predict how many lights would light up in the next moment, let alone what kind of pattern they would form. (For any given number there are of course many constellations with that number of active elements!) At this point we should again invite our philosophers to comment.

I would claim that this is proof of FREE WiLL in Vehicle 12. For I know of only one way of denying the power of decision to a creature—and that is to predict at any moment what it will do in the future. A fully determined brain should be predictable when we are informed about its mechanism. In the case of Vehicle 12, we know the mechanism, but all we can prove is that we will not be able to foresee its behavior. Thus it is not determined, at least to a human observer.

Wait, what? That doesn’t sound like FREE WILL, that sounds like chaos theory/nondeterministic output. Is all free will just chaos in disguise? I kind of like that idea. 😃

Vehicle 13: Foresight

Why shouldn’t we try to modify our brain children, the vehicles, in this direction?

Brain children. That is all.

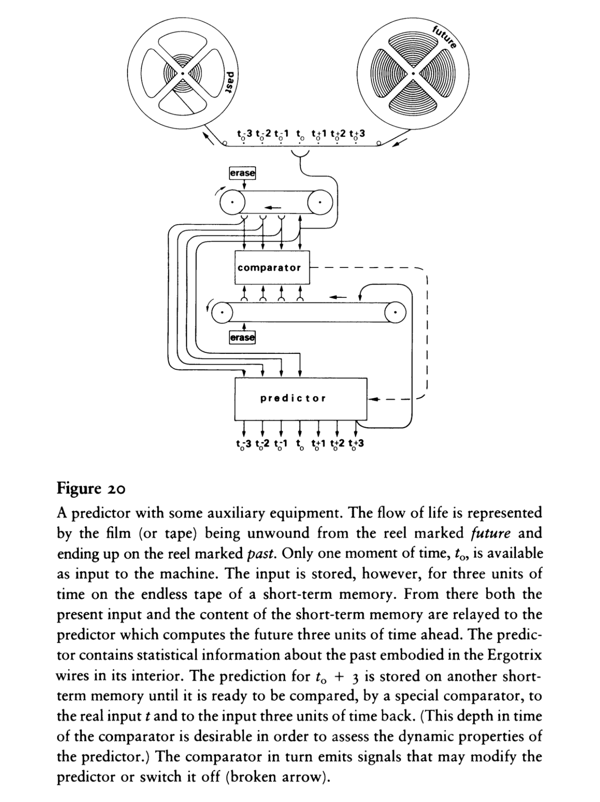

Let us take the first problem first, that of acting toward the future or in accordance with an event in future time. This is obviously nonsense if we take it to mean an action that is now a consequence of something that will happen only in the future. However, it is an entirely different matter—and it does make sense—if we take it to mean an action that is a consequence of something we expect to happen in the future, since that expectation may well be available before the action is planned. There is no violation of the law of causality in this. All we need is a mechanism to predict future events fast enough so that they will be known before they actually happen.

Oh, note that’s interesting. The idea of planning a sequence of actions is one thing, but planning actions based on the outcomes of what hasn’t happened yet but might/should? That’s interesting. I wonder how common that is among animals.

Long term and short term memory! It’s a neat concept to have N values available in short term but to have to shuffle off some of those into long term (or forget them entirely) in order to pull out older memories or try to look ahead/predict.

Vehicle 14: Egotism and Optimism

Give it wants and desires? I’m not sure how this isn’t something that could already arise from the previous vehicles naturally as they grow.

Biological Notes on the Vehicles

So, why did we cross the wires way back in the beginning? Because that’s how our brains are wired, with the left half of the brain controlling the right half of the body.

But why? Something I never really considered. Could be the feedback mechanisms described in those chapters. Could be stability of weaving neurons and brain matter together. Interesting ideas though.