He is interested in the discoveries of science (“intellectual daring and imaginative brilliance without parallel”), the freedoms of democracy (in particular “the great democracy of reading and writing”), the evils of authoritarianism (“always reductive whether it’s in power or not”) and the pitfalls of education (“any education that neglects the experience of delight will be a dry and tasteless diet with no nourishment in it”). He is profoundly interested in religion, while remaining puzzled by aspects of it. “The first thing to say about the Bishop’s arguments in his book,” he writes in “God and Dust,” “is that I agree with every word of them, except the words I don’t understand; and that the words I don’t understand are those such as spirit, spiritual and God.”

Philip Pullman is an interesting author, which makes Daemon Voices an interesting sort of book. In a nutshell, it’s a selected collection of essays and presentation he’s given over the years on a wide range of topics. In particular, he talks a lot about Paradise Lost (makes me want to actually read it), his religious and philosophical views (and a dive into Gnosticism) and how those interact with his writing, and a bit on writing advice and his own particular style.

It’s a fascinating look and there’s a little for everyone, so if you like what Pullman has written, you can certainly do worse than give it a chance!

Below are a few interesting quotes that I highlighted for just about every essay. It’s not really the sort of book where one should worry about spoilers, but just in case that’s not a shared option, you have been warned. (Also: long)

Magic Carpets

THE WRITER’S RESPONSIBILITIES

Well, I’m not going to sell you a pension. I’m just going to say that we should all insist that we’re properly paid for what we do. We should sell our work for as much as we can decently get for it, and we shouldn’t be embarrassed about it. Some tender and sentimental people—especially young people—are rather shocked when I tell them that I write books to make money, and I want to make a lot, if I can.

There’s a lot to be said about that. Authors can write for the love of the craft and the story, but in the end, we still have to put food on the table and a roof over our heads. Something to be said for a patronage style I suppose?

The Writing of Stories

MAKING IT UP AND WRITING IT DOWN

Coleridge, apparently, used to go to scientific lectures to renew his stock of metaphors, and while I would never dream of saying that the main function of science is the production of metaphors for subsequent development in the arts, science is damned useful to steal from.

I do love this idea. The world is weird and wonderful and well worth drawing inspiration from.

There’s no time now to go further into this myth, which is full of psychological fascination, but the thing that was of obvious interest to me was its connection with the story of the Fall, because it’s all about knowledge. There was no single body of official Gnostic doctrine, but some of the sects and cults whose influence wove in and out of early Christian thought (until they were finally rounded up and condemned as heretical) revered the Serpent, which helped Adam and Eve see the truth that had been concealed from them by the false creator-god.

Gnosticism is such an interesting idea… until you start digging deeper. I think that’s true of a lot of religious views (purely my opinion there).

Paradise Lost

AN INTRODUCTION

However, as I say, I was lucky enough to learn to love Paradise Lost before I had to explain it. Once you do love something, the attempt to understand it becomes a pleasure rather than a chore, and what you find when you begin to explore Paradise Lost in that way is how rich it is in thought and argument.

An interesting look into how we teach the classics in schools. Kids never really get into them because they’re so different from what they’re used to and they’re forced to read them. But there’s a reason why many are remembered even today.

So it was, for instance, with the greatest of Milton’s interpreters, William Blake, for whom the author of Paradise Lost was a lifelong inspiration. “Milton lovd me in childhood and shewd me his face,” he claimed, and in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell he wrote what is probably the most perceptive, and certainly the most succinct, criticism of Paradise Lost: “The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils and Hell, is that he was a true Poet, and of the Devil’s party without knowing it.” And Blake’s continuing and passionate interest in Milton resulted in a long (and, frankly, difficult) poem named after the poet, as well as a series of illustrations to Paradise Lost which are some of the most beautiful and delicate watercolours he ever did.

Milton and Blake. I’ve [read the latter](The Complete Poetry and Prose) and need to check out the former. Makes me think more highly of Pullman. Is that weird?

The Origin of the Universe

THE STORYTELLING OF SCIENCE AND RELIGION: A RESPONSE TO A LECTURE BY STEPHEN HAWKING

The trouble comes when the fundamentalists insist that there is no such thing as analogy or metaphor, or else that they are wicked or Satanic, and that there must only be a literal understanding of stories. The Bible is literally true. The world was created in six days. The Kansas Board of Education says so. The worshippers of Bumba, as far as we know, haven’t developed this modern perversion, this modern limitation on the meaning of narrative; it’s only the worshippers of Yahweh and Allah who are as silly as that.

It’s interesting that that’s such a relatively new point of view. And always a problem determining where the line is…

We are the children of the sky-god, or we are made of the same material as the stars.

Either way, stories like this tell us how we got here: but then they say, in effect, “The story continues, and the rest is up to you.”

The Path Through the Wood

HOW STORIES WORK

I expect you can see where this is going. Each novel or story is a path (because it’s linear, because it begins on page one and goes on steadily through all the pages in the usual order until it gets to the end) that goes through a wood. The wood is the world in which the characters live and have their being; it’s the realm of all the things that could possibly happen to them; it’s the notional space where their histories exist, and where their future lives are going to continue after the story reaches the last page.

I like this analogy. Worldbuilding is building a forest, but the story is a path through the forest, and while you may get a great view of a great many trees… that’s not really the story.

(This is the point where practitioners of literary theory will throw up their hands in disgust. Characters don’t have histories, they would say; the only life they have is that in the words on the page; they are not real people, they are only literary constructions; to mistake the characters in a novel for characters in real life is to make a fundamental category error; it’s naïve to the point of stupidity—etc., etc. To these ladies and gentlemen of theory I say, Thank you very much; now go away until you can tell me something useful).

I’ve certainly experienced that myself–characters growing beyond what I started with for them. It’s an absolutely fascinating experience. I guess I’m not cut out to be a ‘practitioner of literary theory’.

I’ve been contacted by people in Canada and elsewhere who have been playing a game that they based on the world I made up for The Golden Compass. It looks like an odd kind of activity to me, but they seemed to be enjoying it. However, I’ve never been a games player of any kind—computer games and card games and chess and Monopoly have never had the slightest attraction for me—so maybe it’s the games-playing cast of mind that you need and I haven’t got.

Fascinating. Games are a huge part of my life. It’s hard to imagine people that just … don’t like games. Even though I suppose I’ve met a few, but all of those eventually ended up playing at least a few games as well.

However, Lyra comes to a different point of view, which by a strange coincidence is also mine: that Dust is a positive good. This does not mean embracing evil instead of good: it means understanding that since the loss of innocence is inevitable, we should welcome it and embrace the next stage of our development instead of hiding our eyes from it. Knowing about good and evil is not the same as embracing evil, though it might look like that to a church that likes to think it has all the answers.

Dust being growing up / Original Sin. It’s certainly an interesting though and gives most of my Catholic friends and family no ends of heartburn I’m sure.

Dreaming of Spires

OXFORDS, REAL AND IMAGINARY

The commonest question writers get asked is: where do you get your ideas from? The truthful answer is: I dunno. They just turn up. But when you are wandering about with your mouth open and your eyes glazed waiting for them to do so, there are few better places to wander about in than Oxford, as many novelists have discovered. I put it down to the mists from the river, which have a solvent effect on reality. A city where South Parade is in the north and North Parade is in the south, where Paradise is lost under a car park, where the Magdalen gargoyles climb down at night and fight with those from New College, is a place where, as I began by saying, likelihood evaporates.

Sounds worth visiting.

Oh, to be so famous that you get that question.

Intention

WHAT DO YOU MEAN?

The aspect of the author’s intention that readers are perhaps most concerned about is the one about “message.” After the first and second volumes of His Dark Materials had been published, but before the third, I was asked many times which of the characters were supposed to be good, and which bad; whom should the readers cheer for, and whom should they boo? They were clearly frustrated by the lack of a clear signal from the author, or the book itself, or the publisher via the blurb, and they felt unmoored, so to speak. The answer I gave was, in effect, “I’m not going to tell you, but the story isn’t over yet. Wait till you’ve read it all, and then decide for yourself. But what are you going to think when someone you’ve taken for a bad character does something good? Or when a good character does something bad? It’s probably better to think about good or bad actions rather than good or bad characters. People are complicated.

They are at that. I do appreciate the shift away from stories specifically having been written for a point and/or you having to figure out (in a classroom setting or otherwise) what that point was to ‘get’ the work. It’s not how I read; it’s not how I write. Good to heard it’s taught less now.

Children’s Literature Without Borders

STORIES SHOULDN’T NEED PASSPORTS

A year or two ago I saw a piece by Robert Stone in the New York Review of Books. He was writing about Philip Roth’s latest novel. Stone opened by praising Roth for his great achievements in the past thirty years, the authority of his voice, his energy, his manic but modulated virtuosity, and so forth. Then he went on to say that Roth was—these are his words—“an author so serious he makes most of his contemporaries seem like children’s writers.”

Oy. It would be interesting to see when this was written and if (for example) the phenomena of Harry Potter has changed that at all.

This impersonality brings me to the second consideration, which is the matter of style. How do you put the words together? What kind of voice are you hearing in your head? What kind of voice does the story want?

Fascinating aside that I came across this year (and may have mentioned elsewhere): not everyone has that voice in their head, at least not their own. I don’t. I always saw that as an artistic device in books/movies; it was quite the experience to realize that it was literally a thing. Now, I can actually construct voices in my head, people reading dialog (or acting their parts I suppose), but in that case, it’s far more conscious / less me than the ‘voice in my head’ is ever described.

Let’s Write It in Red

THE PRACTICE OF WRITING

My eyes were firmly fixed on what I was reading, namely the papers concerning the Centre for the Children’s Book (now known as Seven Stories), which was what I was going to Newcastle for; but the magpie who sits in every storyteller’s head turned his beady-eyed attention at once to what the girls were doing. “What can we steal from this?” he said. “What can we copy? What can we use?”

(Actually, the roosting space in my head is shared between the magpie and another bird: that dusty, broken-down, out-of-date old owl who used to be a teacher. And he opened an eye too, and cocked an ear, if owls can do that, to see what these girls had been taught.)

Children are absolutely wonderful to listen to when they don’t know you’re listening.

Epics

BIG STORIES ABOUT BIG THINGS

Perhaps the epic is in some ways the very opposite of the novel, which began on the page and which really came into its own in the era of printing, as a domestic romance that was enjoyed most happily in solitude and in silence. The oldest epics have something of the declamatory about them: they are more suitably experienced through the ear, perhaps, and in company, than through the eye and in private.

May be worth reading some of those old epics. Viewing them? Listening to them?

Epic heroes, in fact, seem to be at some distance from themselves. This realisation lies behind the crazy and yet tantalisingly rich idea of Julian Jaynes, whose book The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind (Allen Lane, 1976) puts forward the bizarre suggestion that human beings only became conscious in the modern sense during the past four thousand years; that until then, they heard the promptings of conscience, or temptation, or inspiration, as the voices of gods, coming apparently from elsewhere, with no sense that their own minds were responsible.

I’ve heard about the Bicameral Mind before. It such a weird concept–that the ‘voice in our head’ would have felt like the gods speaking, up until we gained consciousness. Actually really anything around consciousness is fascinating to me.

Folk Tales of Britain

STREAMS OF STORIES DOWN THROUGH THE YEARS

And that is the greatest danger for stories such as these: if they remain undisturbed, they will die of neglect. They should be taken out and made to dance. A superb example of the sort of thing I mean is Benjamin Zephaniah’s dub poetry version of the strange old tale “Tam Lin,” set in a world of clubs and DJs and sex in the back of a car and immigrants without official papers. It makes something new out of something old, and the old is still there beside the new, to inspire another telling another day.

Another for my list.

As Clear as Water

MAKING A NEW VERSION OF THE BROTHERS GRIMM

One of the preoccupations of this group was German folklore. Their enthusiasm for this subject resulted in von Arnim and Brentano’s Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Youth’s Magic Horn), a collection of folk songs and folk poetry of all kinds, the first volume of which appeared in 1805 and immediately became popular.

The Grimm brothers were naturally interested in this, but not uncritically: Jacob wrote in a letter to Wilhelm in May 1809 of his disapproval of the way in which Brentano and Von Arnim had treated their material, cutting and adding and modernising and rewriting as they thought fit. Later, the Grimms (and Wilhelm in particular) would be criticised on much the same grounds for the way they treated their source material for the Kinder- und Hausmärchen.

Fascinating. You become what you criticize? And yet, without them, how many would be familiar with those stories even today?

In 1837 came what was probably the most dramatic incident in their lives; together with five other university colleagues, they refused to take an oath of allegiance to the new king of Hanover, Ernst August, because he had illegally dissolved the constitution. As a result they were dismissed from their university posts, and had to take up appointments at the University of Berlin.

There’s just so much history in each and every person’s individual lives that never gets written down. Only a few are remembered, yet even their lives are so much more complicated than a single collection of fairy tales. Fascinating to dig in and read about–when it’s even possible.

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère

MODERNISM AND STORYTELLING

So the thought-experiment that worked with the Yeames fails at the very first hurdle when it comes to the Manet. Long before we get to the difficulty of painting an equivalent picture by reading a description of this one, we can’t even find the words to say exactly what’s there and write the description.

The important things about the Yeames can be put into words: the important things about the Manet cannot.

A picture is worth a thousand words–unless you can’t even start to describe it.

Poco a Poco

THE FUNDAMENTAL PARTICLES OF NARRATIVE

But what are stories made of? Are they made of words? It would be easy to think that they are, because so many stories come to us in the form of words, whether printed or spoken. Words do tell stories, but pictures aren’t bad at it, and even ballet can manage to convey what happens and then what happens next, in a broad sort of way. … which they may happen to be transmitted. I’m going to say straight out that I think stories are made of events, and that the fundamental particles of story are the smallest events we can find. So small, in fact, that they are more or less abstract.

Fascinating. That’s actually something I should probably take note of. I’m very much on the ‘pants’ end of the spectrum with little to no outlining–but the idea that you can outline the events and build a story from that is something worth considering. Those are the building blocks.

And like many other writers, because I don’t know the answer to these questions I tend to be unhelpful or evasive about my answers. “Where do you get your ideas from?” they ask, and I say, “I don’t know where they come from, but I know where they come to: they come to my desk, and if I’m not there, they go away again.” Which may not be helpful, but it is true. The capacity to sit and be bored and frustrated for very long stretches of time is essential, but nowhere near as glamorous as the inspiration idea, and people don’t like to hear about that so much.

Keep notes! There are seeds for stories everywhere!

The Classical Tone

NARRATIVE TACT AND OTHER CLASSICAL VIRTUES

This capacity of the narrator to move from here to there with the speed of thought, to see a whole panorama in one glance and then to fly down like a dragonfly and land with utter precision on the most important detail, to look ahead in time as well as to look behind, is one of the most extraordinary things we human beings have ever invented. We take it for granted, and I think we should applaud it a little more. I don’t know if it makes anyone else rub their eyes in wonder, but it certainly makes me do so; and every time I read a book where the author is so miraculously in control of this ghostly being, the narrator, this voice so like a human’s but so uncanny in its knowledge and so swift and sprite-like in its movement, I feel a delight in possibility and mystery and make-believe.

That’s a neat way of looking at it. The Narrator is (or at least) can be as much a character as anyone who we see/hear on the pages.

Reading in the Borderland

READING, BOOKS AND PICTURES

And it’s a liminal thing—a matter of thresholds. Traversing this borderland is to find oneself between one state or condition of mind, one existential plane, if you like, and another. When I looked up liminality on Wikipedia (in 2010), I found this definition, which I think could scarcely be bettered: it’s a state “characterized by ambiguity, openness and indeterminacy. One’s sense of identity dissolves to some extent…it’s a period of transition where normal limits to thought, self-understanding, and behaviour are relaxed—a situation which can lead to new perspectives.”

The Borderlands is such an interesting space to write in. It’s what makes Urban Fantasy an often favorite of mine. Something just on/past the edge of our own reality.

There’s a subreddit for that. A weird one too.

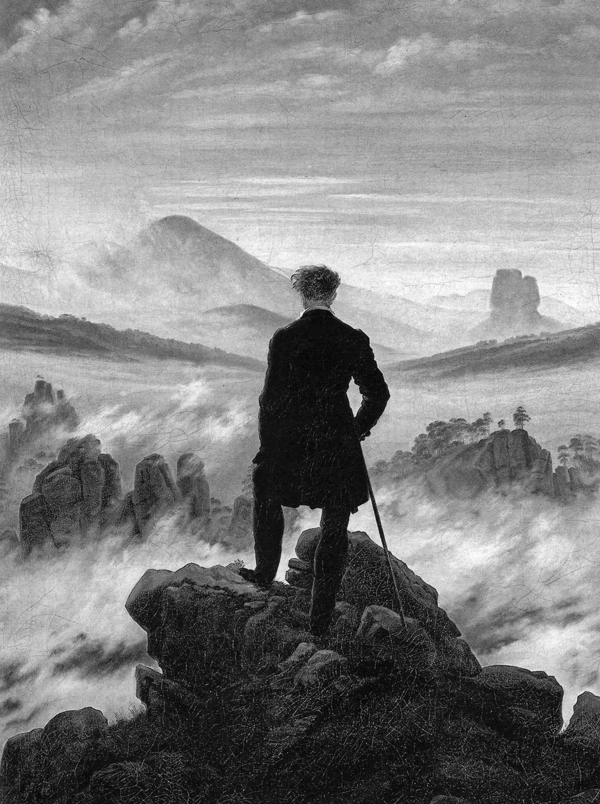

Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich

Oliver Twist

AN INTRODUCTION

From then on, all [Dickens’] novels were to be written and published in serial form. Unlike some novelists, Dickens did not write the whole story before it came out in parts: he really did make it up as he went along. Six months before the serialisation of Oliver Twist came to an end, there were two separate adaptations of it already playing on the London stage, but Dickens said in a letter to one of the theatrical managers concerned that: “Nobody can have heard what I mean to do with the different characters, inasmuch as I don’t quite know, myself.

Serials are such a cool idea as well. You see them a bit with webnovels and a few people have done interesting things with them in self-publishing, but I think we could do with a bit more.

Let’s Pretend

NOVELS, FILMS AND THE THEATRE

I once heard Christopher Hampton make a very interesting point about the novel, and the theatre, and cinema. He said that the novel and the film have much more in common than either of them does with the stage play, and the main reason for that is the close-up. The narrator of a novel, and the director of a film, can look where they like, and as close as they like, and we have to look with them; but each member of the audience in a theatre is at a fixed distance from the action. There are no close-ups on the stage.

Unless you make a film version of a stage play, with close-ups. Then it’s yet another medium entirely!

The Firework-Maker’s Daughter on Stage

THE STORY OF A STORY

A very long time ago, when I was a teacher, I used to write a play every year to put on at my school. It was supposed to be for the benefit of the pupils, but really it was for me.

Lovely.

Imaginary Friends

ARE STORIES ANTI-SCIENTIFIC?

But it reminded me of Dawkins’s misgivings, expressed in a TV news interview two or three years ago, about such things as fairy tales in which frogs turn into princes. He said he would like to know of any evidence about the results of telling children stories like that: did it have a pernicious effect? In particular, he worried that it might lead to an anti-scientific cast of mind, in which people were prepared to believe that things could change into other things. And because I have been working on the tales of the Brothers Grimm recently, the matter of fairy tales and the way we read them has been much on my mind.

…

There’s not just one way of believing in things but a whole spectrum. We don’t demand or require scientific proof of everything we believe, not only because it would be impossible to provide but because, in a lot of cases, it isn’t necessary or appropriate.How could we examine children’s experience of fairy tales? Are there any models for examining children’s experience of story in a reasonably objective way? As it happens, there are. A very interesting study was carried out some years ago by a team led by Gordon Wells and his colleagues at Bristol University and was described in a book called The Meaning Makers: Children Learning Language and Using Language to Learn (Hodder, 1986).

Dawkins is … quite an opinionated sounding man. Gives a solid name and reputation to the ‘militant atheist’. He has a few interesting points though.

Maus

BEHIND THE MASKS

Since its first publication in 1987, Maus has achieved a celebrity that few other comics have ever done. And yet it’s an extremely difficult work to talk about. In the first place, what is it? Is it a comic? Is it biography, or fiction? Is it a literary work, or a graphic one, or both? We use the term graphic novel, but can anything that is literary, like a novel, ever really work in graphic form? Words and pictures work differently: can they work together without pulling in different directions?

Maus as well?! After the discussion around banning it earlier this year and the whole mess that caused, it’s probably worth another re-read.

Balloon Debate

WHY FICTION IS VALUABLE

It’s the myth of Adam and Eve in the garden of Eden.

Now I think that’s a very interesting story, but unlike the Church, I strongly approve of original sin. I think that we should be celebrating Eve, not deploring her. What I was trying to do in my trilogy His Dark Materials was roughly that: to tell that story from a different moral angle, as it were—to tell a story in which Eve was the heroine, and to show a way in which it was possible to see that the knowledge that we gained as a result of Eve’s curiosity—and of the generous, wise and selfless behaviour of the serpent, which risked the anger of God by passing on what it knew—was the beginning of all human wisdom.

Mentioned this before, but it’s certainly an interesting thought experiment at the very least. Who is the champion of free well and self determination throughout the Bible? Who kills countless scores who don’t fall in line?

(Edgy, I know)

And finally, if an atheist may call a distinguished witness, I’d like to refer you to the example of Jesus himself, one of the greatest storytellers of all, who knew that if you want your listeners to remember what you say, tell them a story. Thou shalt and Thou shalt not are easily ignored and soon forgotten; but Once upon a time lasts for ever.

A touch blasphemous… but is he wrong?

The Anatomy of Melancholy

AN INTRODUCTION TO AN INDISPENSABLE BOOK

This book is very long. What’s more, like the book Alice’s sister was reading on that famous summer afternoon, it has no pictures or conversation in it. To add to the drawbacks, parts of it are in Latin. And finally, as if that wasn’t bad enough, it is founded on totally outdated notions of anatomy, physiology, psychology, cosmology and just about every other -logy there ever was.

So what on earth makes it worth reading today? And not only worth reading, but a glorious and intoxicating and endlessly refreshing reward for reading?

If that’s not a reason to give it a try, I don’t know what is…

Soft Beulah’s Night

WILLIAM BLAKE AND VISION

Sometimes we find a poet, or a painter, or a musician who functions like a key that unlocks a part of ourselves we never knew was there. The experience is not like learning to appreciate something that we once found difficult or rebarbative, as we might conscientiously try to appreciate the worth of The Faerie Queene and decide that yes, on balance, it is full of interesting and admirable things. It’s a more visceral, physical sensation than that, and it comes most powerfully when we’re young. Something awakes that was asleep, doors open that were closed, lights come on in all the windows of a palace inside us, the existence of which we never suspected.

Yup. I’ve always liked Blake as well for pretty much exactly that reason.

One such impulse of certainty concerns the nature of the world. Is it twofold, consisting of matter and spirit, or is it all one thing? Is dualism wrong, and if so, how do we account for consciousness? In the opening passage to Europe: A Prophecy, Blake recounts how he says to a fairy, “Tell me, what is the material world, and is it dead?” In response the fairy promises to “shew you all alive / The world, where every particle of dust breathes forth its joy.” This is close to the philosophical position known as panpsychism, or the belief that everything is conscious, which has been argued back and forth for thousands of years. Unless we deny that consciousness exists at all, it seems that we have to believe either in a thing called “spirit” that does the consciousness, or that consciousness somehow emerges when matter reaches the sort of complexity we find in the human brain. Another possibility, which is what Blake’s fairy is describing here, is that matter is conscious itself.

Consciousness + dualism + Blake? Wonderful.

Writing Fantasy Realistically

FANTASY, REALISM AND FAITH

The title of this conference—“Faith and Fantasy”—refers to the third great Christian virtue. Well, here comes the first disappointment: I have to tell you that although I know something about fantasy, and a little about charity and hope, I know almost nothing about faith. I can tell you neither how to get it, nor what it feels like, once got. So I’ve been looking for something to say which (a) doesn’t repeat too much of what I’ve said before; and (b) has at least something to do with your subject; and (c) won’t tread too heavily on what I’ve got in mind to write next. If I talk about the things I’m supposed to be writing about, they disappear. Talking about things I’ve already written about is much safer.

So weird that they got Pullman to do the introduction. But fascinating.

But there isn’t a character in the whole of The Lord of the Rings who has a tenth of the complexity, the interest, the sheer fascination, of even a fairly minor character from Middlemarch, such as Mary Garth. Nothing in her is arbitrary; everything is necessary and organic, by which I mean that she really does seem to have grown into life, and not to have been assembled from a kit of parts. She’s surprising.

Oy. I suppose I’d have to read Middlemarch to make the comparison, but that seems at best a touch harsh.

Fascinating coming from one who many would consider a fantasy author, although he gets into that.

However, if I know anything about writing stories, it’s this: that you have to do what your imagination wants, not what your fastidious literary taste is inclined towards, not what your finely honed judgement feels comfortable with, not what your desire for the esteem of critics advises you to. Good intentions never wrote a story worth reading: only the imagination can do that. So the imagination was going to win here, if I had anything to do with it; and what I had to do to help it win was to neutralise my uneasiness about fantasy; and the way to do that was to find a way of making fantasy serve the purposes of realism.

The Story of The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ

A RESPONSE TO PUZZLED READERS

Never heard of it. Sounds like an interesting read…

So in general I prefer not to discuss the meaning of my work. But The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ is different from the sort of books I’ve published before. It isn’t a novel, not exactly, and yet it’s fiction, or seems to be, but it’s fiction of a sort we don’t often see these days: it’s allegory, of a kind, but not straightforward allegory either. It has become apparent to me that there are readers who are failing to get it not only because they don’t like it, but because they think it’s one kind of thing, and it’s another.

Like I said. An interesting read.

Consequently, the immense and complicated structures of Christian theology seem to me like the epicycles of Ptolemaic astronomy—preposterously elaborated methods of explaining away a basic mistake. When astronomers realised that the planets went round the sun, not the earth, the glorious simplicity of the truth blew away the epicycles like so many cobwebs: everything worked perfectly without them.

And as soon as you realise that God doesn’t exist, the same sort of thing happens to all those doctrines such as atonement, the immaculate conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary, original sin, the Trinity, justification by faith, prevenient grace, and so on. Cobwebs, dusty bits of rag, frail scraps of faded cloth: they hide nothing, they decorate nothing, and for me they mean nothing.

When you have something that has existed for thousands of years… either it’s very right and/or has very powerful backers.

On two occasions, Jesus is represented as being alone. The first is during the temptation in the wilderness, where he encounters Satan, who tries unsuccessfully to tempt him. How did the gospel writers know what Jesus said and did on that occasion? Logically, they could only know if he told them; but does that feel likely? The Jesus we see elsewhere does not tell stories about himself.

The other occasion is when Jesus and three of the disciples, Peter, James and John, go to the garden of Gethsemane on the night of his arrest. He tells the disciples to remain where they are while he goes a little way off, a stone’s throw away, and prays by himself. We are told the words of his prayer, and the Luke writer even says that his sweat became like great drops of blood falling on the ground: pretty much a close-up view. But in all three accounts, in Matthew, Mark and Luke, we are told that the disciples fell asleep and Jesus had to wake them up. If none of them was awake, there was no one to witness Jesus’s prayer, no one to see those drops of sweat like blood, no one to see the angel who, according to the Luke writer, came down from heaven to give him strength. And there was no time afterwards for Jesus to have told the disciples what went on in those anguished minutes, because he is arrested and taken away almost at once, and they never speak to him again. So again: how do the gospel writers know these things?

That’s an interesting point. How did those two particular stories come to be?

That’s the thought-experiment I’d put to every believing Christian: if you could go back in time and save that man from the horrible death of crucifixion, would you or not? And if you think it would be better to let him die so that the church would live, how are you different from Judas?

I’m going to have to try this one…

The Cat, the Chisel and the Grave

DO WE NEED A THEORY OF HUMAN NATURE TO TELL US HOW TO WRITE STORIES?

So what helps me most to write stories is the ability to be profoundly sceptical and profoundly credulous, to be in utterly contradictory states, at one and the same time. Whether or not that’s a theory of human nature I have no idea, but cats can do it.

😄

“I Must Create a System…”

A MOTH’S-EYE VIEW OF WILLIAM BLAKE

But I’ll start with an odd thing that happened to me a few years ago. At that time I was deep in writing the novel The Amber Spyglass, which is the final part of a trilogy called His Dark Materials. Because I’d stolen the name of the trilogy from Paradise Lost, and because the view I’d formed of Milton had been influenced by Blake’s, I was naturally interested in anything that spoke about the two of them. So when I saw a new book called The Alternative Trinity: Gnostic Heresy in Marlowe, Milton and Blake, I bought it at once. It was the word Gnostic that attracted my attention as well. I thought I had the Gnostic thing clear in my mind, but it was always good to have a new point of view.

Another worth reading I believe.

Talents and Virtues

ANOTHER VISIT TO MISS GODDARD’S GRAVE

There is a holy book, a scripture whose word is inerrant and may not be doubted, which has such absolute authority that it trumps every other. Everything, even the discoveries of science, has to be judged against what the scripture says, and if there is a contradiction, the scripture wins. This scripture might be the Bible, it might be the Koran, it might be the works of Karl Marx.

There are doctors of the church, who interpret the holy book and pronounce on its meaning: it might be St. Augustine, it might be the Ayatollahs, it might be Lenin.

There is a priesthood with special powers and privileges, which can confer blessings on the laity, or withdraw them. Entry into the priesthood is an honour; it’s not for everyone; and the authority of the priesthood tends to concentrate in the hands of elderly men: as it might be, the Vatican, or the politburo in the Kremlin.

There is close control of the news media, and ferocious censorship of books. It was the Catholic Church of the Counter-Reformation that invented the word propaganda, and the Soviet Union that took it up with enthusiasm and incorporated it into their term agitprop.

Not a comparison I think a lot of people would be comfortable with.

God and Dust

NOTES FOR A STUDY DAY WITH THE BISHOP OF OXFORD

I would never begin to talk of a person’s spiritual life, or refer to someone’s profound spirituality, or anything of that sort, because it doesn’t make sense to me. I don’t talk about that sort of thing at all, because when other people talk about spirituality I can see nothing in it, in reality, except a sense of vague uplift combined at one end with genuine goodness and modesty, and at the other with self-righteousness and pride. That’s what they’re displaying. That’s what seems to be on offer when they interact with the world. And to my mind it’s easier, clearer, and more truthful just to talk about the goodness and modesty, or about the self-righteousness and pride, without going into the other stuff at all. So the good qualities that the word spiritual implies can be perfectly well covered, and more honestly covered, it seems to me, by other positive words, and we don’t need spiritual at all.

The idea of something people take for granted being truly alien to one’s self is not an unusual concept to me. But this… this bears some thinking about. What is spiritualism?

Firstly, there is the actual reader—the person who buys the book, or borrows it from the library, who carries it home, who sits down, whose eyes actually move over the page.

Secondly, there is the figure known to literary theory as the implied reader—the person the text seems to be addressing.

Thirdly, there is the author—the actual author—the person who thought up the sentences and wrote them down.

Fourthly, there is a figure called the implied author. He or she is the hardest of all these shadows to grasp; the difference between the real reader and the implied reader is easy to understand, but the implied author, though his or her function is real, isn’t quite so easy to get at.

Fifthly, there is the narrator. This is the voice that is doing the storytelling.

I don’t think many people consider the implied reader/author, nor the narrator. Worth considering.

The Republic of Heaven

GOD IS DEAD, LONG LIVE THE REPUBLIC!

…or my books were. An article in the Catholic Herald said that my His Dark Materials was “far more worthy of the bonfire than Harry [Potter]”; it was “a million times more sinister.” Naturally, I’m very proud of this distinction, and I asked the publishers to print it in the paperback of The Subtle Knife.

No press like bad press?

This notion that the world we know with our senses is a crude and imperfect copy of something much better somewhere else is one of the most striking and powerful inventions of the human mind. It’s also one of the most perverse and pernicious. In the Gnostic world-view, it encourages a thorough-going rejection of the physical universe in favour of an unfortunately entirely imaginary world inhabited by evil powers, archons, aeons, emanations, angels and demons of every sort. Tremendously exciting stuff, but all utter nonsense. Just like The X-Files.

Why do I say it’s pernicious? It’s pernicious because it encourages us to disbelieve the evidence of our senses, and allows us to suspect everything of being false. It leads to a state of mind that’s hostile to experience. It encourages us to see a toad lurking beneath every flower, and if we can’t see one, it’s because the toads now are extra cunning and have learned to become invisible. It’s a state of mind that leads to a hatred of the physical world. The Gnostic would say that the beauty and solace and pleasure that can be found in the physical world are exactly why we should avoid it: they are the very things with which the Demiurge traps our souls.

And so it ends with Gnosticism. And unusual one to end up, but still thought provoking.