Ever been to Cracker Barrel? Remember that peg game? It seems that rather a few people are interested in how to solve it: Google. Let’s do that.

Let’s start with a bit of ground work:

; Puzzles are represented as a 15 element vector (#t for pegs)

; but can be entered as a 15 bit integer (1 for pegs)

(struct puzzle (data) #:transparent)

(define (make-puzzle v)

(cond

[(and (integer? v) (<= 0 v 32767))

(puzzle (list->vector

(map (curry eq? #\1)

(reverse (string->list (~a (number->string v 2)

#:width 15

#:align 'right

#:pad-string "0"))))))]

[(and (vector? v) (= 15 (vector-length v)))

(puzzle v)]

[(and (list? v) (length v 15))

(puzzle (list->vector v))]))

It’s a bit heavier than it needs to be (in order to support multiple datatypes), but that saved me all sorts of time in testing. It’s a lot easier to enter a puzzle like this:

(make-puzzle #b111110010000000)

Rather than:

(make-puzzle '#(#f #f #f #f #f #f #f #t #f #f #t #t #t #t #t))

(Note that the ordering is opposite. The highest bit is the last peg, while the first vector is the first peg. This is so that puzzle 1 is peg 1 and so on.)

Anyways.

Next, we need to be able to visualize what we’re working with. You can always see the sequence of pegs, but without putting them in their proper triangular shape, it’s a bit hard to tell what exactly is going on. So first, let’s render a puzzle as text:

; Render a puzzle to text

(define (render-text puzzle)

(for ([row (in-range 1 6)])

(display (~a "" #:width (* 2 (- 6 row))))

(for ([col (in-range 1 (+ 1 row))])

(define i (+ (* 1/2 row (- row 1)) col))

(display (~a (if (vector-ref (puzzle-data puzzle) (- i 1)) i "") #:width 4)))

(newline)))

~a

is rather handy for formatting like this, making sure that each peg (at least the ones still visible) is exactly four characters wide. The formula in the line defining i should look familiar: it’s the sum of the first i integers. Neat.

> (render-text (make-puzzle (random (expt 2 15))))

2

5 6

7 8 9 10

12 13 15

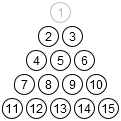

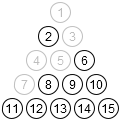

That’s all well and good, but it’s the 21st century. We should be able to make pretty pictures as well:

; Render a puzzle to a bitmap

(define (render puzzle)

(define (bit-set? i) (vector-ref (puzzle-data puzzle) (- i 1)))

(define imgs

(for/list ([row (in-range 1 6)])

(for/list ([col (in-range 1 (+ 1 row))])

(define i (+ (* 1/2 row (- row 1)) col))

(define color (if (bit-set? i) "black" "gray"))

(htdp:overlay (htdp:text (~a i) 12 color)

(htdp:circle 10 "outline" color)

(htdp:circle 12 "solid" "white")))))

(define rows (map (λ (row) (if (= 1 (length row))

(first row)

(apply htdp:beside row)))

imgs))

(apply htdp:above rows))

That’s a bit more complicated. The basic idea is straight forward enough. First, for each peg we’re going to overlay the number as text

on an outlined circle

. The second, white circle is in order to get a bit of spacing. We’ll render each of these into nested lists, each of increasing length. Then we shove each row together with beside

, then the rows together with above

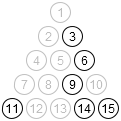

. All that to make a picture something like this:

> (render (make-puzzle (random (expt 2 15))))

Looks good! (And it’s nice being able to see the locations where there currently isn’t a peg as well).

Okay, so now that we have some framework set up, how are we going to attack this problem?

Well, the first thing we need is the ability to make a move. In this case, given two neighboring pegs, jump one over the other:

; Given a peg to move from and the peg to move over, return the new puzzle state

(define (jump p ifrom iover)

(define from-list '(1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4 4 5 5 6 6 7 8 11 12 13))

(define over-list '(2 3 4 5 5 6 5 7 8 8 9 9 10 8 9 12 13 14))

(define to-list '(4 6 7 9 8 10 6 11 13 12 14 13 15 9 10 13 14 15))

(for/first ([from (in-list (append from-list to-list))]

[over (in-list (append over-list over-list))]

[to (in-list (append to-list from-list))]

#:when (and (= from ifrom)

(= over iover)

(vector-ref (puzzle-data p) (- from 1))

(vector-ref (puzzle-data p) (- over 1))

(not (vector-ref (puzzle-data p) (- to 1)))))

(let ([new-data (vector-copy (puzzle-data p))])

(vector-set! new-data (- from 1) #f)

(vector-set! new-data (- over 1) #f)

(vector-set! new-data (- to 1) #t)

(puzzle new-data))))

That’s a bit of an ugly function. Unfortunately, I’m not entirely sure how it could be made better. Still, it works. By virtue of for/first

, we’ll either get the new puzzle or #f if it’s not a valid move.

Next, we take this function and map it over a puzzle in order to generate all possible next states. Something like this:

; Get a list of all next states from a given puzzles

(define (next p)

(filter identity

(for*/list ([from (in-range 1 16)]

[over (in-range 1 16)])

(jump p from over))))

This one though, you should see a fairly easy way to optimize. Right now, no matter how many pegs there are in a puzzle, we’re going to try every neighboring pair. jump can deal with the weird cases, but we shouldn’t have to:

; Get a list of all next states from a given puzzles

(define (next p)

(filter identity

(for*/list ([from (in-range 1 16)]

#:when (vector-ref (puzzle-data p) (- from 1))

[over (in-range 1 16)]

#:when (vector-ref (puzzle-data p) (- over 1)))

(jump p from over))))

That way, the further we get down the puzzle, the fewer cases we will check while still not duplicating too much of the code between the two.

Believe it or not… That’s it. That’s all we need:

; Solve a puzzle using backtracking

(define (solve p)

(cond

[(= 1 (count p))

(list p)]

[else

(let ([n (ormap solve (next p))])

(and n (cons p n)))]))

count returns the number of pegs left on the current board:

; Count how many pegs are left in a puzzle

(define (count p)

(vector-length (vector-filter identity (puzzle-data p))))

That’s it. Give it any peg puzzle and it will solve it. Quickly too. On my machine, it might as well be instantaneous. So how does it work?

Two cases: Either we’re done or we’re not. If we’re done, return the end state. Otherwise, we need to find a state we can move forward from. With ormap, we’re going to try each in turn, returning the first thing that isn’t #f. Since we’re mapping solve (recurring) and almost making progress (next always has at least one less peg), we can rely on the recursion to do it’s job. In this case, we’ll either find a solution one step down (return that one) or not (check the next one).

Don’t believe me? Let’s check it out:

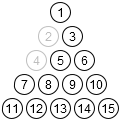

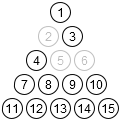

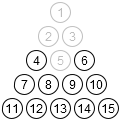

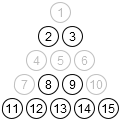

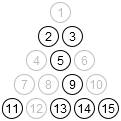

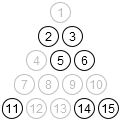

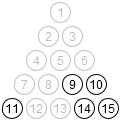

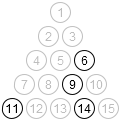

> (map render (solve (make-puzzle #b111111111111110)))

Flip the board over and it looks like we’re genius. 😄 Sweet.

That’s all for today. I am working on a part two though. As a preview: If you take rotations and reflections into account, there are only four possible starting pegs (1, 2, 4, and 5). But it turns out that not all four are created equal–some are (relatively) easy to solve. Some are not.

If you’d like to check out the full source code (and possibly a preview for next time), you can do so on GitHub: pegs.rkt