Today we’re going to be talking about cryptography, specifically Diffie-Hellman key exchange1. The basic idea isn’t necessarily to communicate in secret, but rather to establish the information that makes doing so much easier.

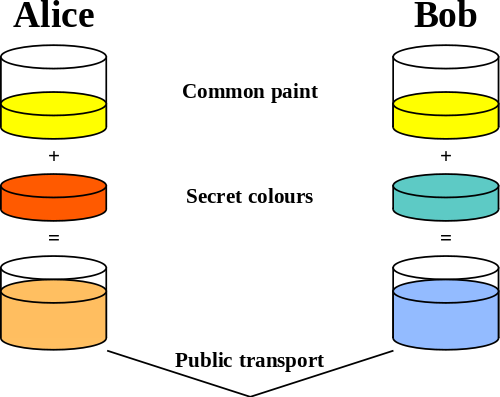

The basic idea behind Diffie-Hellman is actually fairly straightforward. We’ll go ahead and let this nice image from Wikipedia2 illustrate for us.

Assume that Alice and Bob wish to establish some secret key. Better yet, they wish to do so such that no eavesdropper (Eve) can figure out what that key is, even if Eve can intercept any communication between Alice and Bob.

The first step is for Alice and Bob to choose some public piece of information (in this case, yellow paint) and a piece of private information each (red paint for Alice and teal for Bob). They then each mix their private color with the public color. Throughout this process, the assumption is that it is easy to mix paint and that the results for mixing two colors will always be the same, but at the same time it is difficult to separate paints once mixed. It turns out to be true for paint, but also true for modular exponentiation (which we’ll get to shortly). In any case, once both have mixed their paint, they’ll send their mixed paint buckets to each other.

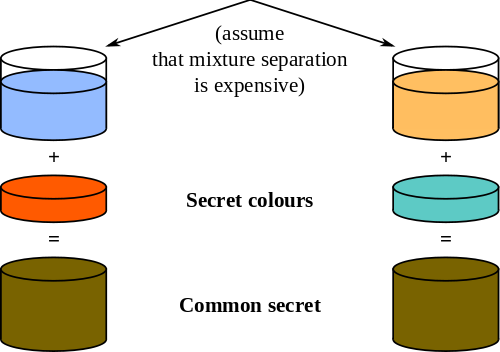

For the next step, Alice and Bob each have their private paint and a mix of the other’s private paint with the shared public color. If they then mix in their own secret, they get this ugly sort of brown3. But the secret is, each will have the exact same ugly shade of brown, since they each mixed the same three colors to get it.

But look back over what was sent. The public information is the shared paint color (yellow) and the two mixed colors (blue and orange). But at no point is either secret color or the final chosen secret shared. What’s more, since you can’t unmix colors and mixing the two secrets will double the amount of yellow, there’s no way to get to that shade of brown from the three pieces of public information. Ergo, Alice and Bob have a (theoretically) secure shared secret.

How could you use it? Perhaps given a paint color, you can make special goggles that can only see that specific frequency. Then Alice and Bob could write whatever they want in ugly brown on other-nearly-identical-but-not-quite brown and no one (but Bob and Alice) would be able to read it. Who knows. The point is, how do we turn this into code?

Well, it turns out that the algorithm is just as straight forward:

| Alice | Bob | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secret | Public | Calculates | Sends | Calculates | Public | Secret |

| a | p, g | p,g → | b | |||

| a | p, g, A | ga mod p = A | A → | p, g | b | |

| a | p, g, A | ← B | gb mod p = B | p, g, A, B | b | |

| a, s | p, g, A, B | Ba mod p = s | Ab mod p = s | p, g, A, B | b, s |

We’re going to need some math / number theory (specifically, the ability to generate a prime number p, calculating a primitive root g, and then performing modular exponentiation. Luckily, we have the math/number-theory

module:

prime?- test if a number is primerandom-prime- determine a random prime number within a given rangeprimitive-roots- return a list of primitive roots for a prime pwith-modulus- functions within this block are performed with this modulusmodexpt- perform fast modular exponentiation

With all of that, we should be good to go. As always, if you’d like to do so, you can follow along on GitHub: jpverkamp/dh.

To make the code a little more interesting, we’re also going to use Racket’s TCP library

. We’ll create a server and client that will set up the Diffie-Hellman secret key.

First, we’ll create the TCP connection:

Client

(define (start-dh-client [server-host "localhost"] [server-port 8000])

; Generate an ID for this client

(dh-debug-id (format "client ~a" (random RANGE)))

; Connect to the DH server

(define-values (from-server to-server)

(tcp-connect server-host server-port))

...

Server

; Create the main server

(define (start-dh-server [port 8000])

; Start listening

(define server (tcp-listen port))

; Accept each client in their own thread

(let loop ()

(define-values (from-client to-client) (tcp-accept server))

(current-thread-id (+ 1 (current-thread-id)))

(thread (dh-client-thread from-client to-client))

(loop)))

(define (dh-client-thread from-client to-client)

(λ ()

; Store the ID for this client

(dh-debug-id (format "client thread ~a" (current-thread-id)))

; Read the shared public values

(define p (recv from-client))

(define g (recv from-client))

; Read the secret from A

(define A (recv from-client))

...

Then we’ll generate the prime p and primitive root g on the client, sending both to the server (send and recv are just wrappers to add some debugging code and make sure that we send a newline and flush after each message; you can find them in dh-shared.rkt):

Client

...

; Generate and share the public information

(define p (random-prime RANGE))

(define g (first (shuffle (primitive-roots p))))

(send p to-server)

(send g to-server)

...

Server

...

; Read the shared public values

(define p (recv from-client))

(define g (recv from-client))

...

Then both client and server will generate and use their secrets along with p and g:

Client

...

; Generate my secret integer, send the shared secret to the server

(define a (random RANGE))

(define A (with-modulus p (modexpt g a)))

(send A to-server)

; Get their half of the shared secret

(define B (recv from-server))

...

Server

...

; Read the secret from A

(define A (recv from-client))

; Generate my own secret number and send it back

(define b (random RANGE))

(define B (with-modulus p (modexpt g b)))

(send B to-client)

...

Finally, both will calculate the secret:

Client

...

; Calculate the secret

(define s (with-modulus p (modexpt B a)))

...

Server

...

; Generate the shared secret

(define s (with-modulus p (modexpt A b)))

...

If all goes well (and there’s no reason to think that it wouldn’t), both will have the same secret. From here, you can do anything you want with the secret. For example, we could use it for the seed in Racket’s random number generator and use that with a basic XOR encryption algorithm to talk completely securely4 (xor-encode/decode are available in dh-shared.rkt):

Client

...

; Use it to seed the PRNG

(random-seed s)

(let loop ()

; Ask the user for input, encode it, send it

(printf "client: ")

(define message (read-line))

(send (xor-encode message) to-server)

; Read a response from the server, print it out

(define response (xor-decode (read from-server)))

(printf "server: ~a\n" response)

; Loop unless 'exit'

(unless (equal? message "exit")

(loop)))

...

Server

...

; Use it to seed the PRNG

(random-seed s)

(let loop ()

; Read a message from the client, print it out

(define message (xor-decode (read from-client)))

(printf "client ~a: ~a\n" (current-thread-id) message)

; Respond politely

(define response

(if (equal? message "exit")

"Good-bye."

"Hello world."))

(send (xor-encode response) to-client)

; Loop unless 'exit'

(unless (equal? message "exit")

(loop)))

...

After that’s all done, clean up the ports we opened and all is well with the world:

Client

...

; Close down the connection

(close-input-port from-server)

(close-output-port to-server))

Server

...

; Clean up the connection

(close-input-port from-client)

(close-output-port to-client)))

And that’s really all you need. Let’s take a look at what each end sees (with (dh-debug-mode #t), see dh-shared.rkt):

Client

client 52989 send (#<output-port:localhost>): 4391

client 52989 send (#<output-port:localhost>): 3813

client 52989 send (#<output-port:localhost>): 3150

client 52989 recv (#<input-port:localhost>): 4132

client: hi

client 52989 send (#<output-port:localhost>): wpfCvQ==

client 52989 recv (#<input-port:localhost>): XnzChcKCEC9Tw6oRd8KHBQ==

server: Hello world.

client: exit

client 52989 send (#<output-port:localhost>): wrvDshI3

client 52989 recv (#<input-port:localhost>): wqvDuHLDtSbCkgsJw4w=

server: Good-bye.

Server

server listening

client thread 1 recv (#<input-port:tcp-accepted>): 4391

client thread 1 recv (#<input-port:tcp-accepted>): 3813

client thread 1 recv (#<input-port:tcp-accepted>): 3150

client thread 1 send (#<output-port:tcp-accepted>): 4132

client thread 1 recv (#<input-port:tcp-accepted>): wpfCvQ==

client 1: hi

client thread 1 send (#<output-port:tcp-accepted>): XnzChcKCEC9Tw6oRd8KHBQ==

client thread 1 recv (#<input-port:tcp-accepted>): wrvDshI3

client 1: exit

client thread 1 send (#<output-port:tcp-accepted>): wqvDuHLDtSbCkgsJw4w=

...

There you have it. You can see the four pieces of information sent (p, g, A, B in that order for either), but with just those four, I challenge you to decode the messages being sent (granted, you can see them, but still…). As a note, I Base64 encoded the messages so that they would be easier to read, but it’s not strictly necessary.

As always, the source code is available on GitHub: jpverkamp/dh. Check it out!

Inspired by the most recent post from Programming Praxis ↩︎

Public domain ↩︎

Here’s where the analogy breaks down somewhat; almost all trios of paint will end up brown… ↩︎

If Racket’s RNG were cryptographically secure (it’s not) ↩︎