So far, we’ve worked out our GUI and I/O and created procedurally generated caves. So what does that leave for today? Something to fight!

If you’d like to start at the beginning, click here: Racket Roguelike 1: A GUI, screens, I/O, and you!

Today’s changes are pretty substantial, so it might be worth it to grab the source and get it handy while we go. In particularly, I’ve added the ⟦ crosslink “a-prototype-object-system-for-racket” “prototype “thing” code” ⟧ from last night, refactored the point code into it’s own file, and created a ‘world’ abstraction to hold things like the player and tiles. I’ll mention each of those in turn, but really not much changed in either, things just moved around.

That being said, what do we need to get everything working?

- Create entity / enemy ’things’

- Create the world abstraction

- Get the enemies moving around

- Entities attack each other when they move into each other

- Entities (and the player) can die

- Logging functionality

So let’s get to it, shall we?

First, let’s use the ’thing’ framework to create some enemies. If you haven’t already read about the system, you probably should. But after that, it should be pretty straight forward. We’ll start with basic entities. An entity is anything that has a location but isn’t a tile in the map. So enemies and (in the future) items:

; entities.rkt

; All entities have:

; - a location on the map

; - attack and defense strengths

; - hitpoints

(define-thing entity

[character #\x]

[color "white"]

[location (pt 0 0)])

Each one has the character and color used to describe it and a location in the world. From here, we can extend this to enemies. These will have statistics for attack, defense, and health, along with an act method that will be called each tick to update the enemy:

; entities.rkt

; An enemy must have an act method

; It should mutate the world with it's updated state

; The default enemy does nothing

(define-thing enemy entity

[name "enemy"]

[color "gray"]

[attack 10]

[defense 10]

[health 10]

[(act me world) (void)])

The real beauty of a prototype based system comes in when we extend that enemy function in turn with a method that implements random movement:

; entities.rkt

; A wandering enemy randomly chooses a neighboring open square

(define-thing wandering-enemy enemy

[(act me world)

; Choose a random possible move

(send world try-move

me

(+ (thing-get me 'location)

(pt (- (random 3) 1)

(- (random 3) 1))))])

We’ll still have to define try-move, but it’s a good start.

Finally, here’s our first enemy:

; entities.rkt

(make-thing wandering-enemy

[name "rat"]

[character #\r])

But all of this is completely worthless if we don’t actually add them to the world. So let’s do that. In order to do so though, this is where we want to factor out the world into it’s own file so that we can keep it separate from the rest of the game-screen% functionality.

In parts, we have:

; world.rkt

(define world%

(class object%

; Store the player

(define player

(make-thing entity

[name "player"]

[attack 10]

[defense 10]

[health 100]))

(define/public (get-player) player)

; Get the contents of a given point, caching for future use

; Hash on (x y) => char

(define tiles (make-hash))

(define/public (get-tile x y)

...)

; Try to move an entity to a given location

(define/public (try-move entity target)

...)

; Store a list of non-player entities

(define npcs '())

(define/public (update-npcs)

...)

(define/public (draw-npcs canvas)

...)

(super-new)))

Let’s go through each function in turn. First, we have the get-tile function. It’s the same thing that we used in last week’s post to generate the map in the first place, but now it’s been extended to generate enemies as well. The trick here is that we tie enemy generation into new tile generation. So whenever we generate a new (open) tile–by moving into unexplored territory for example–there’s a random chance of generating a random enemy as well. So far, we only have rats, but the framework is already there to add any number of enemies.

; world.rkt

; Get the contents of a given point, caching for future use

; Hash on (x y) => char

(define tiles (make-hash))

(define/public (get-tile x y)

; If the tile doesn't already exist, generate it

(unless (hash-has-key? tiles (list x y))

; Generate a random tile

(define new-tile

(let ()

(define wall? (> (simplex (* 0.1 x) (* 0.1 y) 0) 0.0))

(define water? (> (simplex (* 0.1 x) 0 (* 0.1 y)) 0.5))

(define tree? (> (simplex 0 (* 0.1 x) (* 0.1 y)) 0.5))

(cond

[wall? wall]

[water? water]

[tree? tree]

[else empty])))

(hash-set! tiles (list x y) new-tile)

; Sometimes, generate a new enemy

; Only if the new tile is walkable

(when (and (thing-get new-tile 'walkable)

(< (random 100) 1))

(define new-thing

(make-thing

; Base it off a randomly chosen enemy

(vector-ref random-enemies

(random (vector-length random-enemies)))

; This is it's location

[location (pt x y)]))

; Store it in the npc list

(set! npcs (cons new-thing npcs))))

; Return the tile (newly generated or not)

(hash-ref tiles (list x y)))

You may notice that the tiles returned aren’t simple symbols anymore. Instead, they’re another parallel thing hierarchy:

; world.rkt

; Define tile types

(define-thing tile

[walkable #f]

[character #\space]

[color "black"])

(define-thing empty tile

[walkable #t])

(define-thing wall tile

[character #\#]

[color "white"])

(define-thing water tile

[character #\u00db]

[color "blue"])

(define-thing tree tile

[character #\u0005]

[color "green"])

Other than that, the code should theoretically be straightforward. One neat part is that each critter is instantiated as it’s generated simply by using make-thing to extend it (and override the location). This is that nice overlap with extending and instantiating classes that I noted in the prototype post.

What about try-move? Originally, the player movement and the entity movement (in wandering-enemy’s act method) duplicated the code that checked for enemies. But this wasn’t particularly helpful. Instead, we want a method that can handle the three possible cases when moving to a new tile:

- If the tile isn’t walkable, do nothing

- If the tile is walkable and not otherwise occupied, update the location

- If the tile is walkable and occupied, attack the occupant and stay where you are

All of that translates pretty directly to this code:

; world.rkt

; Try to move an entity to a given location

(define/public (try-move entity target)

(define tile (send this get-tile (pt-x target) (pt-y target)))

(define others

(filter

; Only get ones at the target location that aren't me

(lambda (thing) (and (not (eqv? thing entity))

(= (thing-get thing 'location) target)))

; Include the player and all npcs

(cons player npcs)))

(cond

; If it's not walkable, do nothing

[(not (thing-get tile 'walkable))

(void)]

; If it's walkable and not occupied, update the location

[(null? others)

(thing-set! entity 'location target)]

; If it's walkable and occupied, attack the occupant and don't move

; damage = max(0, rand(min(1, attack)) - rand(min(1, defense)))

[else

(for ([other (in-list others)])

; Do the damage

(define damage

(max 0 (- (random (max 1 (thing-get entity 'attack)))

(random (max 1 (thing-get other 'defense))))))

(thing-set! other 'health (- (thing-get other 'health) damage))

; Log a message

(send this log

(format "~a attacked ~a, did ~a damage"

(thing-get entity 'name)

(thing-get other 'name)

damage)))]))

The first part gets the tile and any other entities that could be in the target tile. Right now, there’s no way that more than one entity should ever be in the same tile, but that’s not a hard restriction, it could change in the future.

The second part controls the three conditions. The first two are straightforward, either doing nothing or just updating the location. The last part is a little more complicated because we have to deal with doing damage. For the moment, I’m using a completely made up damage function with a nice degree of randomness:

This means that it’s not possible to do 0 damage and that the minimum attack and defense values are 1. This was a bit of a problem at first, when I used min instead of max on the inner two parts. That meant everything had an attack and defense of 1–which means no one could do any damage. Oops.

Finally, we log the message. I’ll talk about that later.

There are two more parts that we have to deal with, updating and drawing the NPCs. To update them, we have to call each of their act methods in turn then filter out the ones that have fallen to 0 or less health:

; world.rkt

(define/public (update-npcs)

; Allow each to move

(for ([npc (in-list npcs)])

(thing-call npc 'act npc this))

; Check for (and remove) any dead npcs

(set! npcs

(filter

(lambda (npc)

(when (<= (thing-get npc 'health) 0) (send this log (format "~a has died" (thing-get npc 'name)))) (> (thing-get npc 'health) 0))

npcs)))

This does allow for an oddity that an NPC could die during the action loop but then still take it’s turn. It’s suboptimal but on the flip side I think it’s fair. Think of it as the NPCs attack in parallel rather than in turn and everything is fine.

The draw method is pretty much the same. Again, we take advantage of the fact that points are complex numbers and can thus be used mathematically:

; world.rkt

(define/public (draw-npcs canvas)

(for ([npc (in-list npcs)])

(define x/y (recenter canvas (- (thing-get player 'location)

(thing-get npc 'location))))

(when (and (<= 0 (pt-x x/y) (sub1 (send canvas get-width-in-characters)))

(<= 0 (pt-y x/y) (sub1 (send canvas get-height-in-characters))))

(send canvas write

(thing-get npc 'character)

(pt-x x/y)

(pt-y x/y)

(thing-get npc 'color)))))

That’s the majorities of the changes for this week. What’s left is checking if the player is dead, which we do in game-screen%:

; game-screen.rkt

; Process keyboard events

(define game-over #f)

(define/override (update key-event)

(cond

[game-over (new game-screen%)]

[else

...

; Check if the player is dead

; If so, tell the player they lost

; Otherwise, keep on the current screen

(when (<= (thing-get player 'health) 0)

(send world log "You lose!")

(send world log "Press any key to continue.")

(set! game-over #t))

this]))

What this does is check for a game over and then run for one more update so that the player can read the game over message. Then it creates an entirely new game and throws you right back into the fun. The beauty of it all is that everything we had before should all be garbage collected now. That’s the fun of not having to manually manage memory. 😄

Finally, the logging functionality. Optimally, this should be in game-screen%, but a world% doesn’t know about the game-screen% so this is non-trivial to hook up. So world% handles the logging and game-screen% asks it for new messages when it updates.

; world.rkt

; Log messages to display to the player

(define log-messages '())

(define/public (log msg)

(set! log-messages (cons msg log-messages)))

(define/public (get-log [count 1])

(let loop ([i 0] [msgs log-messages])

(cond

[(= i count) '()]

[(null? msgs) (cons "" (loop (+ i 1) msgs))]

[else

(cons (car msgs)

(loop (+ i 1) (cdr msgs)))])))

; game-screen.rkt

; Draw recent log messages

(for ([i (in-naturals)]

[msg (in-list (send world get-log 3))])

(send canvas write-string

msg

1 (- (send canvas get-height-in-characters) i 2)

"green"))

And that’s everything. Perhaps we should get some screenshots? Because screenshots are cool1.

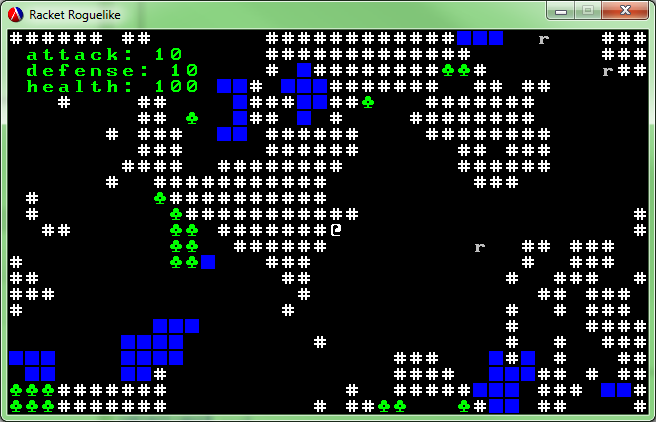

First, we’re just starting out. The caves look much the same (as they should), but now we have a bunch of ratty buddies just sort of hanging out. Since we have a 1% chance per newly generated tile and the map is originally 960 tiles (and a little more than half full) we might expect about 5 rats. I count three and there might be another hidden under the text in the top left, so everything seems good to go.

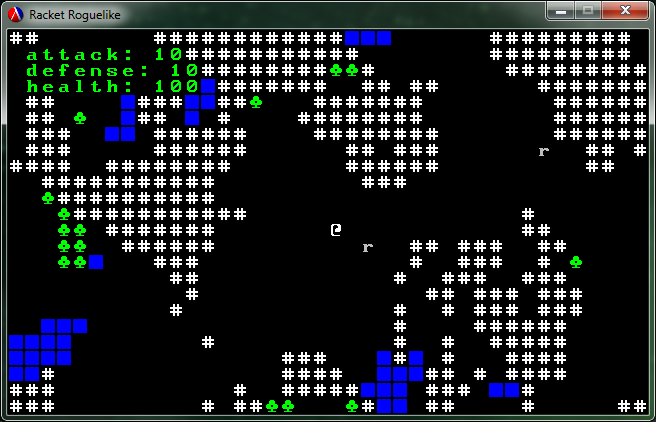

Now we’re chasing down a rat. We don’t have any AI yet, so they’re remarkably dumb. That’s the goal for next week, to have monsters that will either run away from you (as the rats will probably do) or chase you down. This should be one of the more interesting parts of the project.

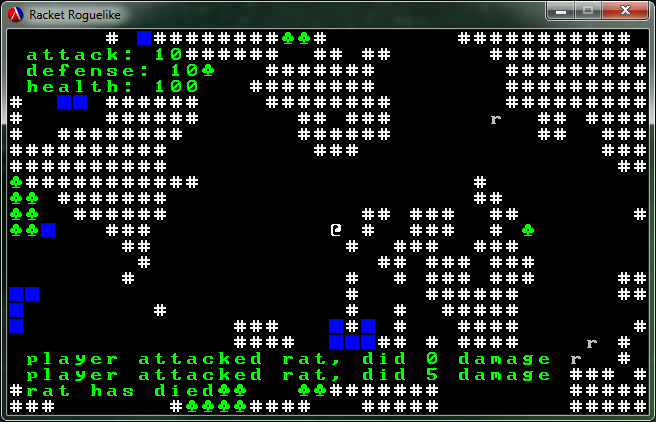

We’ve finally managed to see some real damage here. Interestingly, the monsters can attack each other. I didn’t intentionally plan for this, I just didn’t put in any code that will prevent it. The AI should be smart enough eventually to avoid it, but I think having it as an option is pretty nice. Also, since the rats have equal attack and defense more often than not we shouldn’t see any damage.

Bam. Dead rat. The nice thing is that any NPCs that are killed are removed from the NPC list, so that should help both with efficiency and error checking.

We’re starting to get a bit more afield and there’s just more and more rats. We got another one here, but there are four more just waiting for us.

And finally, the game over screen. I had to add another monster type (the doom) that had a higher attack to actually kill the player in any reasonable amount of time. The rats are just too weak. That’s definitaly a topic for a later article–how do you balance all of this?

And there you have it. Week 3 of writing a roguelike in Racket.

As always, if you’d like to see all of the code for this project, you can do so on GitHub:

If you’d like to try it yourself, you’ll need to have both Git and Racket and run the following series of commands:

git clone git://github.com/jpverkamp/racket-roguelike.git

cd racket-roguelike

git checkout day-3

git submodule init

git submodule update

racket main.rkt

Edit:

It seems that the submodules wondered off at some point. Instead, you can install the three libraries this uses directly using pkg

, and then run the code:

raco pkg install github://github.com:jpverkamp/ascii-canvas/master

raco pkg install github://github.com:jpverkamp/noise/master

raco pkg install github://github.com:jpverkamp/thing/master

git clone git://github.com/jpverkamp/racket-roguelike.git

cd racket-roguelike

git checkout day-3

racket main.rkt

If you already have the code, you’ll still have to init and update the submodules since I added a third one. Theoretically, I should be using PLaneT for this instead, but that’s something to put off for another day.

For part 4, click here: Racket Roguelike 4: Slightly smarter critters!

I may or may not have been watching Doctor Who for the last few hours… ↩︎